In preparing for this month’s newsletter, I read through my previous ones to help me get back in the groove. It’s been a while, afterall, and, truthfully, my mind has been mostly elsewhere this past year. I’ve written about the Molisan folklore around spring, what the season has meant through time and how Molisani take the time to celebrate it in the present; about lace-making, the time-consuming and centuries-old tradition of merlettaie in Isernia; about gardens and the time spent in backyards; and about moving back to my childhood home, into the apartment where I spent my first years.

Over the past year, in conversations about the cookbook project I just completed with the Federazione delle associazioni molisane del Quebec, I often found myself talking about time, in both its depth and superficiality. At a surface level, people are interested in knowing the time it took to finish the project (or why it took that amount of time). How many years, days, hours, did you dedicate to the work? And you find that, no matter the time it took, you always want more; you can find so many ways to have spent that extra time. What I’m interested in though, are the deeper reflections on time that have emerged from this project and from most of the writing I’ve done here so far.

A few years ago, I remember reading something about the practice of cooking in Ancient Rome.1 And that, no matter how we try to recreate the recipes in present, that practice will never be exactly the same. A lot has to do with ingredients and the technology we use for cooking, of course. But the other aspect mentioned was time. The time that had to be dedicated to preparing food, like grinding flour or fermenting crucial ingredients, was part of the act of eating. And, in fact, to eat, one had to dedicate a certain amount of time that we don’t really have the space, patience, or need for today.2 This time spent fundamentally changes the relationship to food and eating.

I think about my lunches instead and how, especially when I’m working, I try to find the quickest way to consume something, anything. I’m very much a victim of “girl dinner” snack and ingredient platters to get me through the day. There is no time dedicated to the act of feeding myself because, in that moment, I think, it’s not worth it. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with preparing something quick and easy - and, let’s be honest, sometimes you just gotta do what you gotta do - beyond our separation from our ingredients,3 by also separating ourselves from the prep and the time needed, what connection do we have to food, besides eating it? I’m not saying anything groundbreaking, but this all clicked the other week when I was working on a current contract. Someone present at the workshop I was documenting talked about feeding yourself and how “it gives you at least three opportunities to enjoy your day.”4 What a beautiful way to see it, I replied.

Talking to people about their traditional recipes and cooking, they often bring up the idea that taking the time is part of enjoying your meal. Things like labours of love, enjoying the fruits of one’s labour, etc. fall into the scope of making good food. That homemade not only tastes different, but feels different. And makes you feel different. At this same workshop, we talked about the ability to feel through food:

food sharing and feeding are important non-verbal indicators of friendship and romantic involvement. […] shared meals are an important aspect of courtship behavior, with people eating together more frequently as commitment increased. Sharing meals with relatives was found to be the primary way to become acquainted with one another’s family – and served as a signal that the relationship was becoming more serious […]. Taken together, these findings underline that people perceive food sharing as an important indicator of – and means to establish and increase – intimacy, friendship and love.5

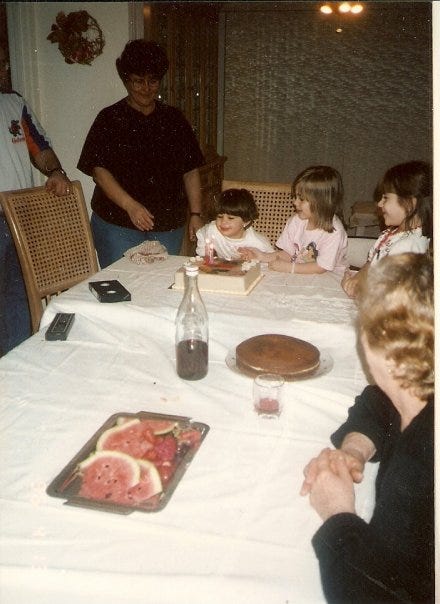

Time spent around the table, therefore, is often experienced as quality time. And it just so happens that, in my practice as an oral historian, my work has almost always taken place around the kitchen table. Whether about food or not. The kitchen table is not only a family space, but also a place where we invite others in. We gossip there, eat too much there. We sometimes sit alone there. It’s dynamic, yet static; it’s a site of tradition and change, as we try new recipes, invite new partners, use new table cloths.

Tradition is also a word I’m always unpacking along with the concept of time. Traditions seem and feel timeless, but are actually rooted in the present in order to make a connection with the past. When we speak of traditional Molisan food in the present, we are speaking of a context where we have the choice to make it. In having and making that choice, a simple dish of polenta and beans - macche e ffasciuol - takes on a particular meaning it did not have in my nonni’s homes when they were growing up. Even calling it macche e ffasciuol, in the dialect, has a particular meaning, in a context where many don’t have ties to that language anymore.6 Do traditions move through or against time, fighting to stay rooted in a place that was not built for them? How do we build their place in our world?

On la festa di Sant’Antonio (Jan. 17) in Frosolone, a small mountain town in Molise, celebrations are held in his honour. Traditionally, after mass, people would bring their animals to the front of the church, where they would be blessed by the priest. They would then head home to make the food offering, called lessata. The most traditional and rustic version is simply boiled corn kernels in salted water. They would be drained, and the family would eat some before sharing the rest with their animals, which is why the recipe had to be kept simple.

I learned about lessata when I interviewed Giovanni, a man who immigrated to Montreal from Frosolone: "Eravamo amici degli animali." We were friends of the animals, Giovanni explained as he told me about this shared meal.

Most families would have one pig for the year, unless they worked with livestock. The head would be used to make gelatina (the feet, too, though those could be eaten separately). The skin and lard would be used for cotiche. The legs would be cured into prosciutto. Innards, like the stomach, were used to make trippa. The ribs and stripped bones could make bollito. Even the hooves would be used to make buttons.

There was a duality: being friends with animals, and then eating almost every single part of them. It was also a reality in which a family most likely had access to only one pig a year. One that had to be shared between at least four people. My nonno told me his memory of the taste of lard rubbed on bread. The taste of the last of the family pig. Each moment of your relationship with that animal traced through a specific timeline throughout the year. What would that pig mean to you?

This is a story that I think and talk about often. Because, firstly, when Giovanni explained it to me, it made me cry. So I wanted to unpack that. But also because so many of these stories served as a stark reminder against romanticizing this past. And that is a constant balancing act I am facing, too: appreciating what we can learn from this way of life, from this relationship to animals, nature, and food; what we can learn about how people spent their time; and how we can root that here in meaningful ways to bring community together and share. To be an active part of our lives, traditions cannot be left to steep in nostalgia because it doesn’t put us in a position to grow and learn. As we move through time, as our knowledge grows, we - hopefully - adapt.

Another conversation I’ve been having a lot recently centres around the meaning and purpose of doing this work: why write about, think about, recipes, dialects, folklore? Who cares? Is it really what is important right now? And this, too, brings me back to time. These have been my reflections when discussing this point with fellow Italian-Canadians doing this work: unfortunately, our community/ies (because we are many different communities under the umbrella of “Italian-Canadian”) have not always done a great job of documenting ourselves in the past. Or, in some instances, if that documentation has existed, it hasn’t been preserved accordingly. Having had experience on the archival side of all this, I’ve learned that so much is missing from the historical record (especially on first-wave immigration; those who arrived in the late 19th and very early 20th centuries). While we have time, with our nonni and elder community members, we must do what we can to safeguard the stories, documents, objects, photographs, that tell of our everyday lives. And we have to do this unselfishly, prioritizing accessibility and collaboration.7

The reality is, I feel the weight of time often. I fear running out of time, losing to time, and not making the right choices about how I spend my time. In fact, one of my resolutions this year is to host more, and spend more time inviting people around my table. This has felt good. I’ve even tried to embrace the cleaning afterwards, which has always stressed me out as a “waste of time.” That one is more difficult.

But I’ve discovered that spending time with friends, old and new, in this way is a balm to the fear of not having enough time to learn everything I want. Because knowledge is shared in community; this is the lesson I have continuously found within every story or tradition shared with me through my work. So even when time wins (because it always does), if I remember that, and choose to live with that spirit in all that I do, I can never really lose.

Cass

See below for monthly tarot pull, footnotes, and resource list.

Monthly Tarot Read

Each issue will include a tarot pull reflecting on the research and folklore discussed in the newsletter.

The Castle is material comforts, protection, and power. But, in its darkness can also be a fortress of solitude, dark and cold. In her prompt for this card, Kim Krans writes:

Notice how castles are designed to keep things out. They defend. They separate. It is likely there is connection and community beyond its walls that will revitalize you.

This is an invitation to look outside ourselves and our egos. Along with the Vision - our imagination, our purpose - this month’s pull reminds me that making meaning in our lives should be collective work. If you haven’t, I invite you to read the last three paragraphs above because this is the point I was making. We are each on our individual search for what brings us joy and meaning; we may each be questioning ourselves, wondering how this vision could possibly be significant for anyone else. Or, we may guard ourselves, hoarding what is precious in order to feel like we are in total control. But something special happens when you connect with another person’s vision(s), something that sparks and revitalizes your own. Something that allows you to grow and think and push yourself. And the beauty is, you don’t have to do it alone.

I really can’t remember if it was on Tavola Mediterranea or an Historical Italian Cooking video caption. Or it could have even been somewhere else - if this rings a bell for you, let me know where you saw it, please!

Of course, we can decide, should like, to mill our own flour and take this time. However, it isn’t really the average person’s experience with food and eating.

I’m speaking from the context of someone in an urban environment who is lucky enough to have some direct connection to ingredients grown in our family garden and food items that are prepared by hand/preserved for the year. However, for the most part, in urban North American contexts, we are quite divorced from our ingredients: where they come from; what the soil they grew in is like; how they’re prepared and preserved; the conditions they are kept in, etc.

A little footnote to say one way that helps me get excited to start my day is oatmeal. No, really. Lately, I’ve been making myself pumpkin pie or PB&J oatmeal in the mornings and I always look forward to getting out of bed and having breakfast. Today, I’m actually having salted caramel cream of wheat.

Myrte E. Hamburg, Catrin Finkenauer, and Carlo Schuengel, "Food for love: the role of food offering in empathic emotion regulation,” Front Psychol. 2014; 5: 32. Published online 2014 Jan 31. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00032.

A fellow Italian-Canadian of Molisan descent is starting some interesting work on Molisan dialects on his Instagram page lengalonga.

In another chat with fellow oral historians, we also talked about how collaboration isn’t always as glamourous as we make it out to be. As with all relationships and interactions, collaboration is hard. But it’s too important to avoid navigating.

Resources

Hamburg, Myrtle E., Catrin Finkernauer, and Carlo Schuengel. “Food for love: the role of food offering in empathic emotion regulation.” Front Psychol. 2014; 5: 32.

Published online 2014 Jan 31. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00032.

Hobsbawm, Eric and Terence Ranger, editors. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Kitchen Work. “The Home Cooking Issue.” Winter 2024; 9.

Marco Gavio De Rubeis. Ancient Roman Cooking: Ingredients, Recipes, Sources. I Doni delle Muse, 2020.

Marsillo, Cassandra and Vee Di Gregorio. Dalla valigia alla tavola: A journey through Molisan culinary heritage. Montreal: Federazione delle associazioni molisane del Quebec, 2023.