Before getting into these reflections, as someone who has studied migration and Canadian history, I am deeply aware of the connection between immigration (both the physical acts of movement and settlement, and all the legal, bureaucratic procedures behind it) and colonization in this country. The privilege to garden on this land — Tiohtià:ke (Montreal) — comes from this history and legacy.

First of all, I’m sorry for the delay in getting this month’s newsletter to your inbox. Turns out that moving while working a few jobs is… a lot. While all the boxes are unpacked, as I began writing this, there were still things strewn across the living room and lining the hallway that needed putting away. And just to give you an idea of how much stuff I have, my dad texted me this while picking up the last load of items from our old place just over a month ago: “Cassy don’t get mad but you have to get rid of some of this stuff.”1 By the time you’ll be reading this, all will have been settled in its place, as this newsletter is a product of the entire month of July, written in moments when the move and that end-of-semester lack of motivation (yes, it affects teachers, too), left me enough energy to do so.

Since we moved, we’ve picked the first tomatoes, made our first jars of pesto, my mom has shared the first batch of kale with all of us, my aunt has brought boxes of spinach, and my nonni have supplied us with so many (yet somehow never enough) zucchini flowers. The Italian garden, with its tomato, basil, escarole, cucumbers, and pepper plants, is an icon of culture and tradition in and of itself. These gardens serve as the basis for simple, but hearty, summer meals. For many, they are also fundamental to year-long sustenance, supplying fundamental ingredients for the cold months ahead: passata and pelati,2 peperoncini sott'olio (hot peppers in oil), giardiniera, and other pickles or preserves.

Being back in Saint-Leonard has been nice. One of the best parts has been coming back to u ciardine. We’ve had an increasingly large balcony garden over the last three years,3 but this is the real thing. This is home. I love looking out and seeing that familiar (and oh-so-typical) view of neighbours’ clothes hanging to dry, metal spiral stairs, overhead power lines, and the family garden below. This one, too, has grown over the last few years as my mom has started planting kale for her smoothies; my dad has started a little homemade hot sauce hobby;4 and now we’ve added the remains of our balcony herbs and veggie plants to the yard, as well. I want to spend more time in this beautiful backyard, but it’s hard keeping up with time, isn’t it?

Every day that goes by, I feel our fleeting Montreal summer inching closer and closer to fall, wishing that I had spent more time outside and less in the office from which I am writing at this very moment. I’m often reminded of the advice many folks gave me when I was doing my oral history interviews for a food history project I’m working on: “Gardens take a lot of time. Start small. You will get overwhelmed and you won’t have time to take care of it.”5 The burden of “taking care of the garden” is definitely not mine,6 but I already feel a certain pressure (to at least learn) as my to-do lists never dwindle as much as I expect, and every day — rain or shine — is spent indoors putting things away, prepping classes, grading, or working on projects.

Like taking months-long trips and joining a variety of dance or card-playing social clubs, it sometimes feels like maintaining a full-scale giardino is meant to be a privilege of old age and retirement. And I will join the queue of people asking: why must we wait until then to live?

Doing this project on the stories and recipes of the molisana community in Montreal has been one of the most enriching experiences of my life. Despite the stereotypical image of the nonna who greedily guards her recipes from even her own children, let alone a stranger calling in the middle of a pandemic, I’ve found folks to be quite open to sharing, teaching, and getting involved. One woman even said we should put her phone number in the book in case people have questions. Obviously, we won’t be doing that, but this is the perfect example of the spirit behind this work.

What I’ve learned from these interviews and my own personal experiences around the hesitancy to share is that, despite wanting to uphold and pass on traditions, handing the keys of knowledge over can also sometimes mean losing your role in the family, or community. If you’re the one who prepares the traditional Christmas dessert, giving that recipe over to your grandchild means stepping aside to help them learn — botching and perfecting — until they get it right under your watchful eye.

If we’re growing our own escarole and zucchini, then it would be redundant for my nonno to share his crop with us. We bug my nonna because she always manages to pick all the ripe veggies before we have a chance to even set foot in the garden. But if we do it ourselves, then she won’t have all that bounty in her fridge to distribute among the rest of us in the “complex” (the name we have given to the family triplex we’re all living in).

It’s bittersweet. The need to preserve and document requires us to face our mortality, or that of our loved ones, as we scramble to remember against the unforgiving passage of time.

“There is nothing better than having a nonno, and I should know: I had two of them. Nonnos are no-nonsense, hardworking and cheeky. They know how to fix things, how to make things, how to grow things, how to care for things. They basically know all the things. They can keep their family in health supply of fresh, homegrown food all year round. Their thriving gardens pump out produce from fence to fence.”7

It’s a funny place to be in because everyone recognizes the importance of that knowledge: you, your parents, your grand-parents. And yet, somehow, sometimes, it stays stuck behind a wall:

”But why do you want to know? We do it for you.”

”But you don’t have to do this, you can just go buy at the store.”

”When will you have time to do a garden?”

”I’ll do it for you, you don’t have to worry.”

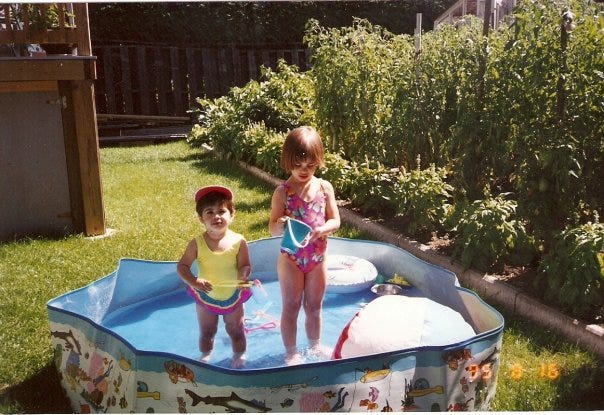

All of these things are true. And while, at the end of the day, I can spend some time Googling and watching videos on YouTube, it’s their knowledge that is a part of me. It’s that knowledge that I want to cherish. Their hoses that watered the garden, filled our little pools, and quenched our thirst (is there some scientific explanation as to why water from the backyard hose is so much more refreshing?). Their seeds that gave us so much that we took for granted as children. Their labour that I want to understand.

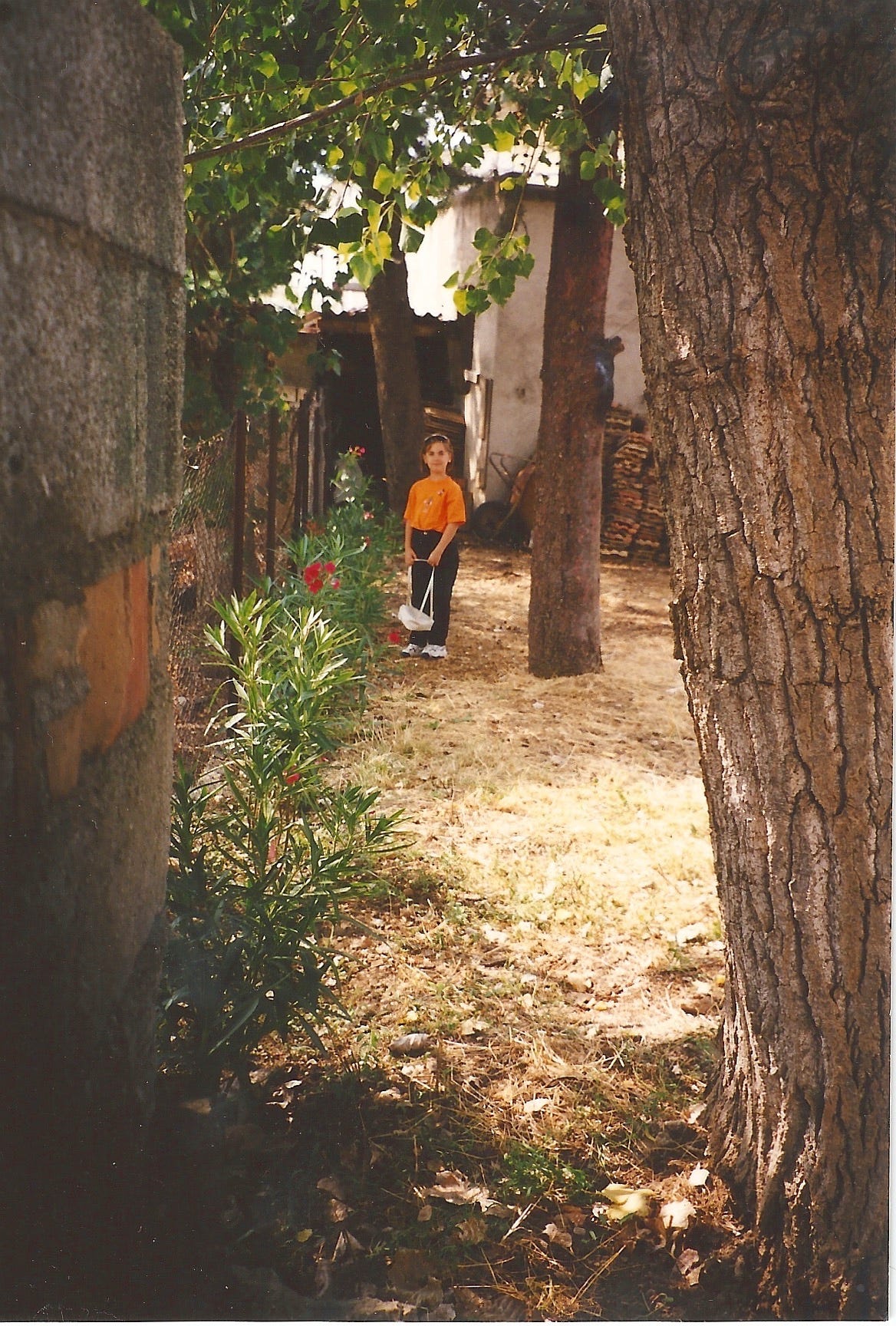

The Italian-Canadian garden is a product of immigration. It tells that story, too. Maybe more than any other. Backyard gardens didn’t exist in the paesi my nonni called home. The yard beside the house might have been used to grow some herbs, which were used daily, like basil, oregano, or maybe even a bay leaf tree.

Other fruits and veggies were grown in fields or orchards, which could be quite a few kilometres away from the home. Those who didn’t have their own fields sometimes worked for others who did, and many folks have told me stories of their mothers preparing large lunches for all the family’s fieldworkers. In Santa Maria, my great-grandfather’s olive trees, which he used to make oil and weave baskets, still stand. I’m not sure how many generations tended to them. There’s land somewhere else, too, but no one seems to be able to identify where exactly it is.

The gardens growing in suburban Montreal are a micro-reproduction of that land. Some folks go through great lengths — burying fig trees for the winter, for example — to connect to that authenticity.8 They mark a presence in a landscape that felt as different from village reality as could be. Though smaller than the fields back in Molise, they represent “making it”: moving out of the duplex and triplex apartments many rented upon their arrival, to a house. Both the home and the garden, monuments to the sacrifices made to leave and begin again.

And this, again, comes back to us. The ‘future generations.’ I think a lot about what “making it” meant for my nonni. It’s not just about them: “We sacrificed for you.” We’ve all heard it before. Making it also means that their children, grand-children, and beyond, have also made it by proxy. My nonni went from a context where they needed to farm to survive, to one where they garden as a hobby and to share food with others. If I’ve made it by proxy, I shouldn’t have to do either of those things.

A few people contacted me after last month’s newsletter, especially responding to the idea I used to hold that moving “back” to the family home in St-Leo meant that I had failed at “making it.” We exchanged a few messages around this belief and how “making it” under capitalism moves you further and further away from community, because a world of individual consumers is more profitable. The Italian-Canadian garden needs to survive if even only to fight against this distancing. Because growing food is the complete antithesis to facing the world alone. As the constructs around “making it” seem less attainable every day (housing markets… cost of living… job precarity…), I’m feeling more at peace with my life as it is. Not always and not completely. But more. Another thing that takes time: unlearning.

All these reasons — and probably much more — are part of my desire to learn more about Molise, gardening, and traditional recipes. And, above all, my desire to be less busy so that I can actually follow through on that knowledge. I’m going to make some garden peppers for a late lunch now.

Cass

See below for monthly tarot pull, footnotes, and resource list.

Monthly Tarot

Each issue will include a tarot pull reflecting on the research and folklore discussed in the newsletter.

The Page of Pentacles, like the suit of Pentacles in general, speaks to material (often financial) life. However, Pentacles also represent the element of Earth: grounded, nurturing, tangible. The suit of Swords is the element of Air: moving, transformative, invisible. The Six fo Swords tells the story of a mother and child on a journey across turbulent waters towards a safer, more comfortable future. So many of today’s reflections are coming up for me here. The most difficult aspect of tarot pulls for me is putting all those swimming thoughts out of my head and on paper in a clear and cohesive way. This is part of practicing through these newsletters.

Migration is about those hopes for something different, something better. It’s about that child in the boat. Migration carries baggage — those six swords — that we often think the act of moving will allow us to leave behind. Yet, they linger. For the mother and the child, who was too young to understand them in the first place. Moving forward — progress, a word I spend a lot of time trying to unpack in my day to day life — that will make things better.

When faced with the Page of Pentacles, the sign that big dreams or goals are manifesting, it’s easy to fall in the trap that word creates for us. Progress — “forward or onward movement toward a destination” — is starting to feel more limited. The destination(s) set by progress are few, and deviating from those set guidelines feels like a betrayal to that baggage, that journey to a safer place.

Air and Earth together remind us that stability can also be found in transformation. That we can stay grounded, but move away from the visions for our futures that have been implanted in us from those inherited hopes and dreams. That, actually, we need to unsheathe those swords one by one rather than pretend they are no longer relevant to our lives. Because maybe that baggage is the idea of progress that has been constructed through the generations. And it’s time to let that go. Shedding the baggage and expectations of progress, life becomes less individual.9

The Page of Pentacles is not just about manifesting goals, but about identifying and developing the skills necessary to achieve them. Earthiness is creative, dirty, life-sustaining. Look beyond the expected and connect with that side of you. Perhaps gardening is too on the nose, but if you’ve been thinking about it, do it. Embody it: ask questions; connect to neighbours, family, and friends who have been growing their own gardens of all sizes; share your bounty; use your fresh herbs as much as possible.

Passata being “smooth” tomato sauce and pelati a chunkier one, as it consists of whole tomatoes with the skin removed (hence the name pelati, which literally means peeled).

Our balcony garden got so big last summer, that we struggled to seat four people among the plants. And there was more than enough room on there for four.

With a mix of peppers that he has bought, planted, and harvested, and some plants gifted from his Laotian colleagues. This, too, is the garden: sharing seeds, traditions, cultures.

Or my favourite advice from my nonno yesterday: “Vogliamo tutti fare l'agricoltore. Facciamo solo del nostro meglio.” We all want to be farmers. But we just do our best.

Though it is one we will all share now that my nonna has gone to Italy for two months.

Jaclyn Crupi, Garden like a nonno: The Italian art of growing your own food (Affirm Press: South Melbourne, 2021): 15.

Hal Klein, “Why Bury Fig Trees? A Curious Tradition Preserves A Taste Of Italy,” NPR, December 25, 2014, https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2014/12/25/371184053/why-bury-fig-trees-a-curious-tradition-preserves-a-taste-of-italy.

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing tackles this beautifully in her 2015 book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins.

Resources

Bellissimo, Stephanie. “Standing with my Forefathers: Reflections on Italian Canadian Experiences and Identity.” Canadian Heritage Matters. September 26, 2016, https://canadianheritagematters.weebly.com/heritage--history/standing-with-my-forefathers-reflections-from-the-pier-21-museum.

Canadian Museum of History. “What Italian Canadians Most Often Grow

in Their Gardens.” https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/cultur/presenza/pszaz26e.html.Canadian Italians Against Oppression. “Cucina Povera Instagram Guide.” https://www.instagram.com/ciaomtlorg/guide/cucina-povera-series/18206323006095064/.

Crupi, Jaclyn. Garden like a nonno: The Italian art of growing your own food. Affirm Press: South Melbourne, 2021.

Di Nardo, Ari. Filo Rosso Blog. https://aridin0.wordpress.com/.

Giuliani-Caponetto, Rosetta. “From Garden to Table: Cultivating Southern Hospitality through Italian American Gardening Traditions.” Diasporic Italy: Journal of the Italian American Studies Association (2021) 1: 84–102. https://doi.org/10.5406/27697738.1.1.084.

Howard, Rob. “Couple's Italian-style garden has fed the family for half a century.” The Hamilton Spectator, August 15, 2016, https://www.thespec.com/life/homes/2016/08/15/couple-s-italian-style-garden-has-fed-the-family-for-half-a-century.html.

The Italian Garden Project. https://www.theitaliangardenproject.com/.

Klein, Hal. “Why Bury Fig Trees? A Curious Tradition Preserves A Taste Of Italy.” NPR, December 25, 2014, https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2014/12/25/371184053/why-bury-fig-trees-a-curious-tradition-preserves-a-taste-of-italy.

Sciorra, Joseph. Italian Folk: Vernacular Culture in Italian-American Lives. Fordham University Press: New York, 2010.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press: New Jersey, 2015.