Sunday Story #7

Revisiting an unpublished piece about childhood, magic, religion, and storytelling

I’m back with a late Sunday Story this week, as I’ve been settling in to a new schedule and lifestyle due to starting my side gig subbing elementary school. It’s been fun and the kids are hilarious, but definitely requires some getting used to as it is a different type of energy from my usual day-to-day. I’m also in a mental creative boom phase and have been drawing a lot, so I sometimes let way too much time slip away from me while I’m working on something new. Oops.

This past week, I was looking through my old writing and found a piece I had worked on during an incredible storytelling workshop hosted by Herban Cura and led by Mandana Boushee in November 2020. I would like to revisit it today, as I find myself thinking more about my writing and storytelling; what I want to do with it; where I want to take it/it to take me.

Here is an edited version of the piece I wrote and read for one of our sessions that November:

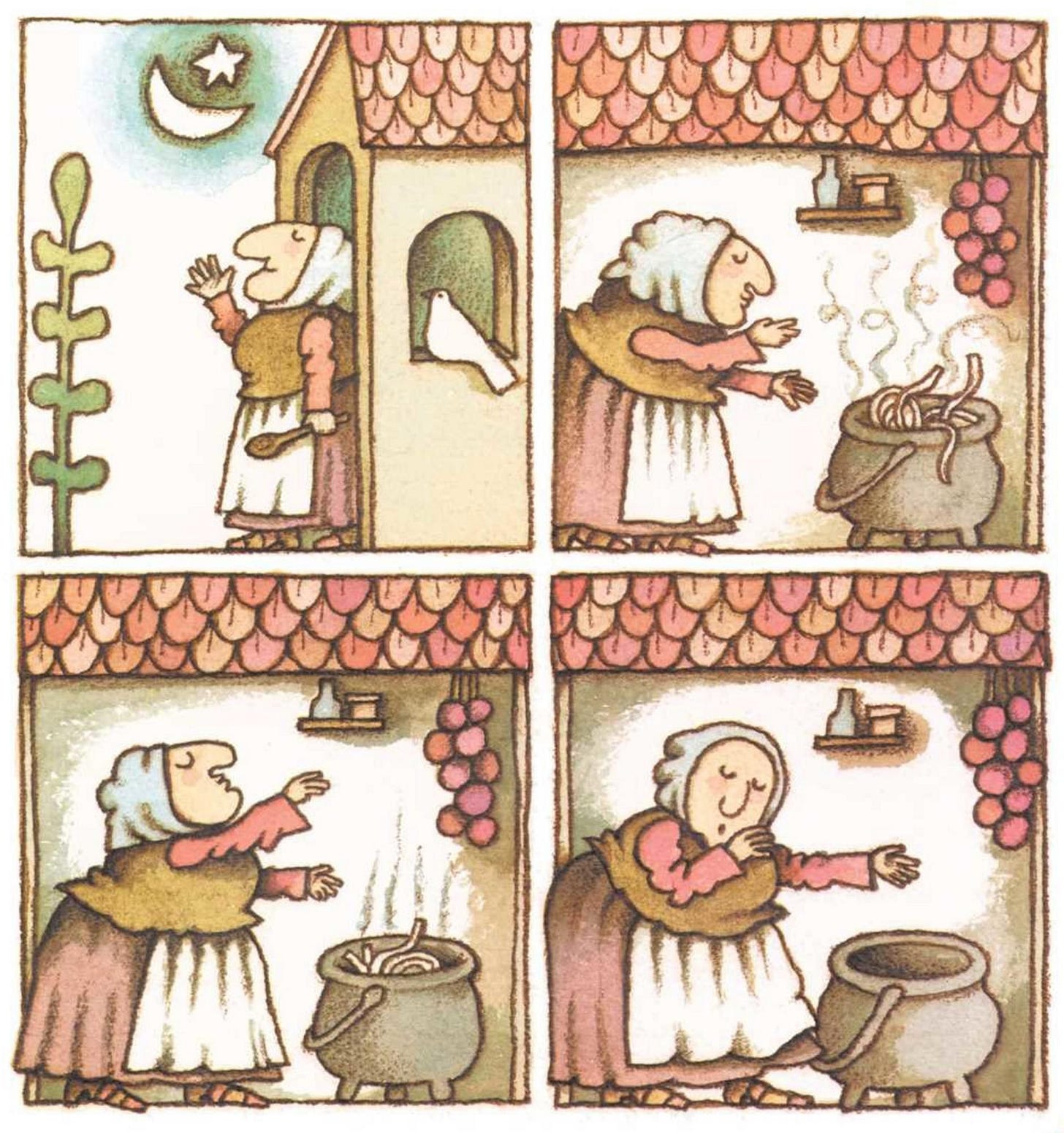

Last night, my boyfriend and I listened to a recording of Tommie dePaola reading his children’s book, Strega Nona. It’s a book that many Italian-American and Italian-Canadian kids had - or still have - on their shelves today. It tells the story of an elderly woman living in a small town in Calabria. The villagers called her strega nonna (spelled nona in the book) - or grandma witch - as she was known for her magic touch.

“She could cure a headache,” goes the story, “with oil, and water, and a hairpin. She made special potions for the girls who wanted husbands. And she was very good at getting rid of warts!”

The most magical of all, though, was her special pasta pot that, should you say the correct incantations, cooked a potentially infinite amount of pasta on its own.

We listened and laughed, and I felt that nostalgic satisfaction one experiences when sharing something precious from their past with someone who has never known it. My boyfriend grew up in Italy, in a city just outside Milano. Often, we don’t have the same pop culture references. Strega Nona is one of those cases. We also have very different experiences of “being Italian.” He, growing up in the north, just thirty minutes away from one of the biggest cities in the country. I, growing up in one of the biggest cities in so-called Canada, with roots and traditions from a small southern Italian village, which my great-grandparents left in the 1950s.

When we finished listening to the story, he looked at me and said: “magic is very much intertwined with the Italian South, isn’t it?”

I have a vivid childhood memory of lying on my nonni’s green couch in their living room, in the dark, with a bad headache. The smell of my nonno’s cologne wafting off the cushions, as it always did. My mom was whispering to my nonna in the other room. A phone call was made, though I didn’t hear what was said. Five minutes later, my nonna leaned over, caressed my forehead and told me that I should be better soon.

I didn’t know at the time, but they had called my zi’ Anna because they suspected mal’occhio, the evil eye, was the cause of my headache.1 We must have gone to some party or event earlier that day: that’s peak mal’occhio breeding ground.

No one really told me what was going on. Mal’occhio is this thing that people see as a superstition, while also fearing it. It’s not to be made fun of or meddled with by children. “Non e vero, ma ci credo.” That’s what countless people have told me when I ask them about their belief in the evil eye: “It’s not true, but I believe it.” And so, it remained this mysterious magic to me for a long time. Like strega nona’s hairpin and oil cure.

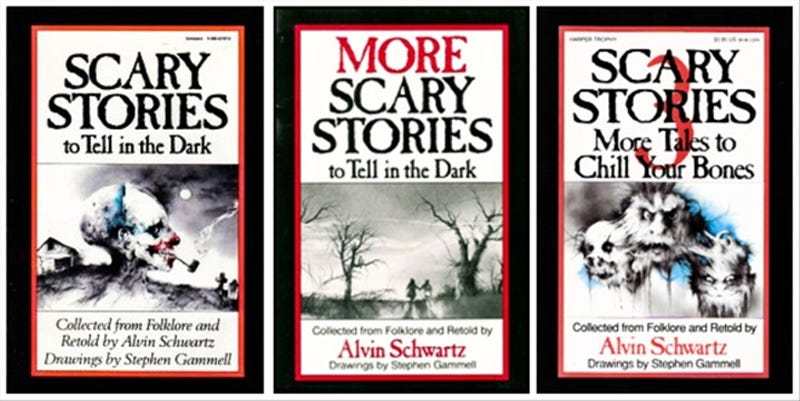

To say I was obsessed with magic and the supernatural as a kid is an understatement. In each Scholastic’s Book Club flyer from school, I would circle three things: the latest diary - preferably with fancy lock and key -, the latest magic kit, and Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (or other latest story about hauntings). Plus probably four to five other books. I have always been naively optimistic: there’s no way I would ever be allowed to order that much in one go.

Like many kids, I was interested in the “unknown.” And though it was a very superficial understanding of magic - full of ghost hunting, haunted houses, and card tricks - it engaged me in so many ways: through reading, my own writing,2 role play and acting, and - though I didn’t know it yet - connecting with the magical roots of my culture. And like many kids, I was open to this magic in ways that I rejected as I got older.

I was a religious child. I loved mythologies and legends, and stories of ancient gods and goddesses, and the stories of the Bible helped build that world for me. Religion was also part of growing up Italian: bedtime prayers were in Italian - padre nostro, ave Maria - repeating after my nonna as she tucked us in; festivals held in parks for Sant’Anna and Santa Maria; masses and candles for the dead in November.

My nonna kept a poem I wrote about Jesus when I was a kid, maybe as proof that I could be saved or that I was once a “good Catholic girl.” This, too, I rejected as I got older and as discomfort grew towards the institution that I saw as antithetical to so many things I believed true and just in the world around me.

Digging Deeper

I studied fine arts and history. And now I tell stories in classrooms. I listen deeply to stories told through my oral history practice and I weave stories together in my work as a public historian. I interpret and analyse; I bring primary sources to life; I collaborate and build relationships and share complex narratives. And I’ve finally come back to an understanding I already had buried within me in my rejection and cynicism of the magic I lived as a child, a concept my ancestors knew, and many traditional knowledge keepers have known: that the past, present, and future are intertwined. That history is not the past, but the interpretation of this web of time. That the work of historians is not to tell the past as it happened, exactly as it happened - because that is an impossible task - but to craft a narrative, to tease out this knot, or even tangle it further.

History as an academic discipline was built on falsehoods in order to gain acceptance in the allegedly objective and sterile halls of the academy. It was presented as a science, based on observable facts and impartial data taken from unbiased sources, presented as absolute empirical truth. Memorization of dates and textbook passages ensued. I love teaching and doing the work of history because I love undoing this idea. I love watching my students stop memorizing and start analyzing, interpreting. “Doing” history is mental and sometimes physical work, depending where you have to go find your sources; it can’t just be memorized on flashcards.

There are many things that I let go of and let wither away as I got older and I find myself, now, figuring out what I want to grow back. At this moment, this has partly manifested for me through food, gardens, and cantine - the practice of keeping a cold cellar filled with pickled, preserved, and cured meats, fruits, and veggies. This September,3 for the first time in many, many years, I spent two days with my nonna making and jarring tomato sauce. I made wine with my nonno, dad, and uncles, which we celebrated with our old tradition of eating my nonna’s pizza after crushing all the grapes. I am speaking to family friends and community members about traditional and ancient dishes from our region, Molise, and the stories behind them, learning about the relationships they had with the land, plants, animals, and food. Of the bay laurel that grew through the cracks of old buildings. The buttons made from the nails of pigs because nothing went to waste.

And, this summer, I tended my first garden. We don’t have a yard, but we have a balcony big enough for a raised garden box and many pots. We filled them with herbs and veggies. We failed at growing lettuce. Our basil plants were disappointing, but we learned lessons and watched as our tomato plants grew daily. We sat by the garden, our hair in the tomato leaves. I love that smell.

I my time home, alone, with no courses to teach and nowhere to go, I am trying to figure out where and how I can let this magic flow from me again. I was drawn to tarocchi, tarot. My mom bought me my first pack back in March.

Many of my friends have done readings for me before and I love the combination of the artistry, history, spirituality, and storytelling behind the practice. And only recently, after getting my first deck, did I learn about the historical presence of tarot cards in Italy. In the 15th century, they were mostly used and commissioned by the aristocracy in the north, from which the suits of cups, coins, swords, and polo sticks (now wands), developed. I read that they were used for a game known as “tarocchi appropriati.” Players were dealt random cards and would use the cards and their imagery to write narratives about each other.

I don’t think that it’s a coincidence that I would be drawn to this practice. The interpretation, the storytelling, sharing narratives - it’s so much like the work I do when I teach and do history. When I do a reading for myself, and the cards are revealed, it’s the same feeling I get in an archives or during an oral history interview, as I literally feel my insides working, churning - gut, brain, heart - to understand the stories, choices, images, voices before me. I was taught that these are different from each other: using your brain, or following your heart, or trusting your gut. When actually, they work together in almost magical ways. You physically feel them trying to reach each other.

What are ways that you recall feelings of magic from childhood? How do you put them into practice?

What is your favourite way to tell stories?

Many cultures have some representation of the evil eye: do you have something similar to mal’occhio in your culture? How do people react to it today?

Cass

Mal’occhio, or the evil eye, is some kind of affliction, oftentimes a headache, which is given to someone, usually unintentionally, through another person’s envious thoughts or words. In 2016, I interviewed 5 mal’occhio healers in Montreal - 2 third, 2 second, and 1 first generation Italian-Canadians - on their understanding of and feelings towards their practice. I published a chapter on this project in a collection called Offstream: Minority and Popular Cultures, edited by Paola Bernardini, Paolo Frascà, and Sara Galli. I also wrote about my experience with zi’ Anna’s story specifically, which you can read here.

RIP to my unfinished horror novel, The Sand-Witch. I wrote the first chapter in a Hilroy notebook in elementary school.

September 2020.

I’m grateful that my feelings of magic as a child never left me. I was born in the middle of the witching hour the day before Halloween, so liminal spaces have always been my favorite places to hang out. I remember telling my parents that I wanted to be a fortune teller when I grow up and I’m happy to say that I have grown up to become many things, including a fortune teller of sorts (a Conjurewoman and astroherbalist). I love being a conduit between the spirit and physical world. The work is heavy, but my ancestors help me keep it light and come up for air.