Being Italian-Canadian growing up in Saint-Leonard, a suburb in the east end of Montreal, meant that half our street was occupied by paesans and cousins. In elementary school, if my maternal nonni, Lucia and Michele, weren’t in Florida, going south for the winter - aka being snowbirds, as we say in Québec - lunch was at their house, down the street from ours. If they were on vacation, after school was at Jo’s, down the street from them, where my sister, Erica, and I were always greeted with: “Do you want a Coke and Jos Louis?”

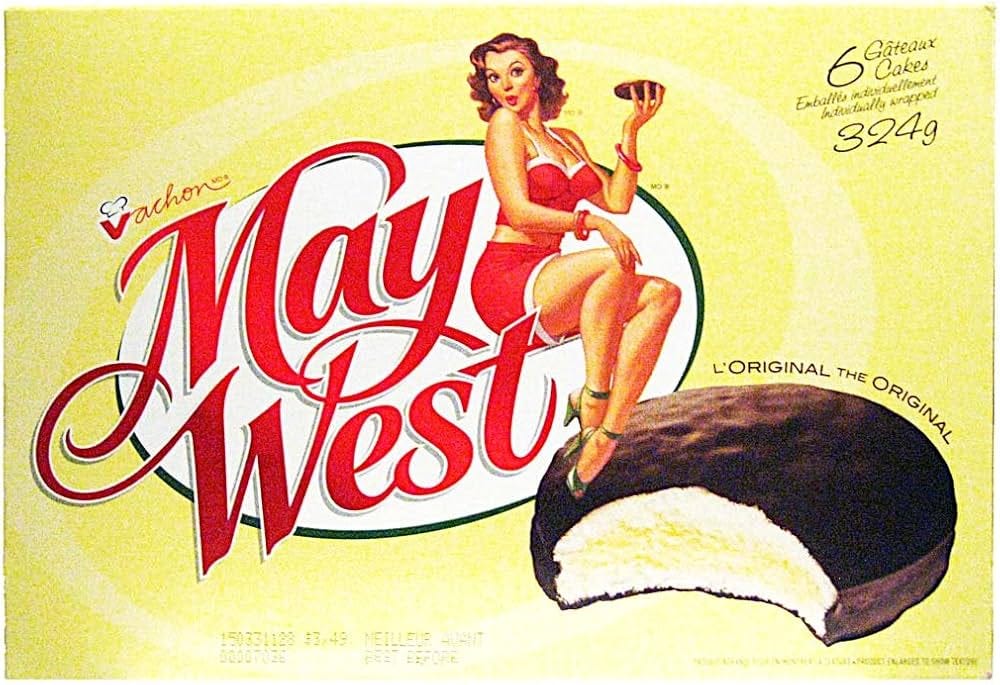

I never really liked soft drinks, so I would pass on that. But Vachon’s Jos Louis, May Wests, and Passion Flakies were treats I never said no to.

Though we had been spoiled with homemade Italian cakes and cookies since we were born, there was something special about these sickly sweet goodies, manufactured by an iconic Québec-based company. Both the Jos Louis and May Wests are little, round cakes covered in a thin layer of chocolate and stuffed with cream fillings. May West is vanilla cake with vanilla cream; Jos Louis is chocolate cake with a marshmallowy fluff. Passion Flakies were love at first bite for me: a pastry layered with apple-raspberry jelly and whipped cream.

I wish they were actually as good as I remember them being. Although, maybe that’s just the memory of Jo’s care for us.

Jo - nickname for Giovanna - was Nonno Michele’s first cousin. She was one part of the large network of “unofficial babysitters” we were lucky to have growing up. They each spoiled us in their own way. At Jo’s, it was with snacks. Forget about asking for “just some water.” It was unacceptable. “At least a juice!” she would reply. Through her kids, who are older than us, we also learned about pop culture beyond our years. We would rifle through their CDs and listened to the Vengaboys’ The Party Album for the first time in Jo’s basement. We would beg her son to play on his Game Boy, because we didn’t have any video games at home. As we settled in with our snacks, we would finish watching Jo’s soaps with her. I believe the favourite was Days of Our Lives.

Just to give you an idea of what kind of a person Jo was: she continued to give us baggies of chocolates and money on Halloween well into our twenties. My sister and I cherish the memories of afternoons at Jo’s. And it’s precisely those memories that got me thinking about the significance of snacks. Though Italians are often characterized as turning their noses at anything that’s not “like my mamma’s,” my introduction to snacking, fast food, and Québecois treats came from older Italian immigrants.1 Like Jo with Vachon products, Nonna Lucia with Harvey’s and hot dogs, Nonno Michele with oreilles de criss, and Nonno Bart, my paternal great-grandfather, with KFC.

As a freelance historian, I have decided to keep my newsletter subscriptions free in order to share my writing with whoever has an interest for the research and reflections in these posts.

If you’ve been following along and have enjoyed my work, liking the posts by clicking the heart at the bottom of the page is easy way to support me.

I’m not interested in moral arguments around “junk food” and snacks. There are so many more compelling things to explore. Though labelled as “junk” or “garbage,” snacks like Vachon’s Jos Louis have a local, family history. Sometimes, these snacks can take on cultural baggage so large that it comes to define generations. Sometimes, these snacks—as incomparable to nonna’s cookies as they may be—have more emotional weight and personal meaning than the most traditional of recipes. I want to explore (in today’s “Digging Deeper” and beyond) how snacks are opportunities to cross cultures and histories, and sometimes even rebel against expectations of what is “good” or “proper.” In the particular case of Québec and Vachon pastries, I am interested in how we can be defined, redefined, and undefined by what we eat and where we eat it.

Digging Deeper

After the Second World War, as many Italians flooded into the country, “industrial capitalism […] transformed Canadian society, as the manufacturing of non-essential products escalated.”2 Increased prosperity and work hours changed the food scene: snack foods, according to Janis Thiessen, were no longer seen as “treats,” but as “replacement or supplementary ‘meals.’”3 The number of Canadians snacking, and the number of snacks they ate, steadily increased throughout the decades.4

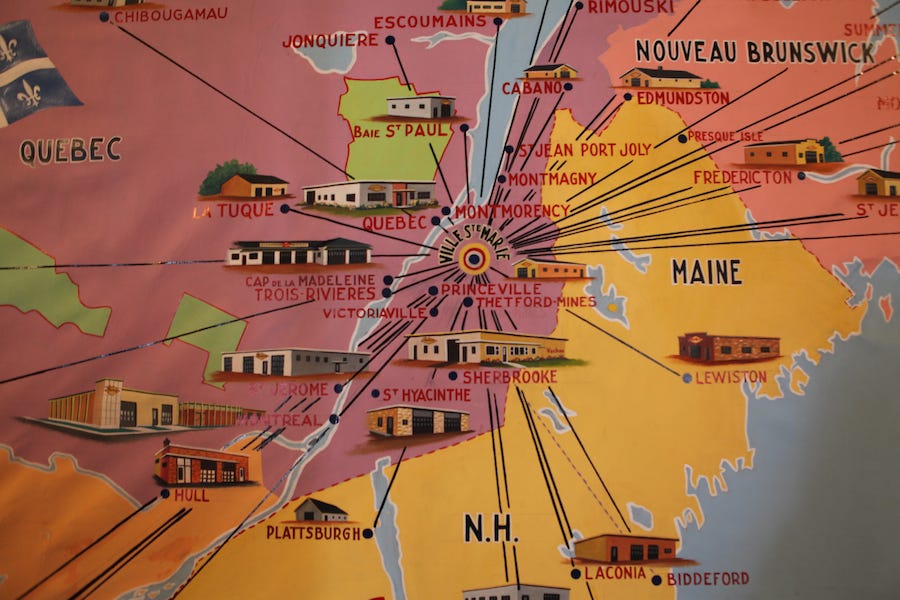

This is echoed in the Vachon company’s own history, as their industrial era began in 1938, when they outgrew their old bakery in the village of Sainte-Marie-de-Beauce, Québec. The family bought out an old shoe factory and—inspired by their son Joseph’s experience working in American mass production assembly lines—crafted their own automated conveyor belt by sewing together empty flour and sugar bags.5

The Vachons started their business in 1923, when they bought a bakery from a widow who could no longer run it on her own. In the beginning, they only sold bread locally, in competition with the parishes. By 1927, J.A. Vachon & fils, had overtaken their competitors and added pastries, made by their matriarch, Rose-Anna, to their deliveries.

Legend goes that the famous Jos-Louis (named after two of the eleven Vachon siblings, Joseph and Louis) was created by Paul Vachon in 1932. The shape and size was determined by the makeshift cutter he used: the lid of a baking powder tin.

By the time Jo, and many other Italian immigrants, settled in Montreal, Vachon had long made a name for itself throughout Québec. Though I don’t know why Jo had a particular attachment to their snack cakes, I know that she came from the same reality as my own nonni: decadent desserts were saved for special occasions only. Cocoa and chocolate featured in Christmas cookies and rarely, if ever, during the rest of the year. Sweets were homemade, and not available individually packaged at the corner store.6 In 1950s Québec, Vachon snack cakes were selling for $1 a dozen.7

Of course, had my great-grandparents never left Italy, my snack cake references would have been different. Recently, The Muffa shared an interesting post on the Italian merendina boom of the 80s and 90s:

Our connection to Vachon snack cakes is also complicated by their use as an insult towards French-Canadians. I’ve written about it before in my pâté chinois post: in a context where different cultures and communities co-exist, identity can be insulted through the food you eat. The insults I used as examples in my previous post—maudits spaghettis (damn spaghettis) for Italians and pea soups for French-Canadians—can still be heard today. Another insult thrown towards Québecois is “Pepsi May West.”8 Pepsi because it was apparently a little cheaper than Coke (but also because it has always been particularly popular in Québec, compared to elsewhere).9 And May West because it was a favourite offering of Vachon’s in the province.

Therefore stating that not only did French-Canadians eat junk, but they drank it, too. This insult, as with all food-based insults, was morally loaded: you are what you eat.

By the time I was a kid, the context here had changed quite a bit. We were past the initial tensions. I have never in my life been called a maudit spaghetti and myself and my friends did not grow up using the terms “pea soups” and “Pepsi May Wests.” For me, Jos Louis are as much a part of my history as mustaccioli. And while the circumstances for Jo’s generation were much more difficult, the snacks and fast food they added to their diets fundamentally altered the way they shaped their identities. Like all of us immigrants and children or grand-children of immigrants in Québec, navigating identity means a convoluted journey between at least three languages, histories, and cultures.

There is a feeling of cognitive dissonance because I have so many shared cultural touchpoints with Québecois (and as an allophone10 who went to English schools, I am not considered one), because I grew up here. A big part of my identity is the fact that I am from this place, which has marked my experiences, with education, pop culture, food; with the way my community speaks and the stories my nonni have shared.

Not to put so much weight on a simple Jos Louis, but my childhood snacks are a part of that.

I don’t know what these snack cakes meant to Jo. Maybe she just had a sweet tooth and took a liking to them. I wonder what she would make of this newsletter. Would she tell me that I’m overthinking things? Or would she feel similarly about the snacks she adopted upon immigrating here? Either way, I’m sure we would chat about it at the table, over a Jos Louis and anything but water.

Jo passed away in 2019, leaving a legacy of love and warmth in the memories of all those who were lucky enough to know her.

Cass

What was your favourite snack as a kid? Does it have a particular history?

Tell me about traditional snacks from your culture.

If you would like to support my work further, you can

(it’s like giving a tip) or share Crivello with a friend! Thank you for following, commenting, sharing your stories, and even simply continuing to open these emails week after week.

News

For subscribers, and as a way to practice my tarot skills, I’m offering a one card tarot pull for the new year. It will be a general message for 2025, which I will send via voice notes on Instagram. Send me a dm to coordinate, if you are interested!

Not to mention my own childhood taste, which some may call questionable:

Janis Thiessen, Snacks: A Canadian Food History, p. 6.

Ibid.

As a little personal anecdote, I’ve seen this cultural difference between my boyfriend and I. Having grown up in Canada, I am very pro-snack. I need to have a selection and variety of snacks to choose from to keep me going throughout the day. On the other hand, he grew up in Italy and doesn’t have the same affinity for granola bars as I do. For him, the one appropriate “snack” is an aperitivo (like a small charcuterie board, some taralli, or chips) when we get home from work.

Dave Corriveau, L’histoire des p’tits gâteaux Vachon, 1923-1999, p. 50.

Vachon was part of this change in Québec, as before Rose-Anna started making her pastries for the family business, sweets were typically made and eaten at home, too.

Dave Corriveau, L’histoire des p’tits gâteaux Vachon, 1923-1999, 84.

Here is a short piece on the phenomenon: https://maisonneuve.org/post/2010/02/4/how/.

This has been attributed to the fact that Pepsi really leaned into their popularity here and invested in specialized ads made specifically for Québec with their 1984 Claude Meunier campaign.

In the Canadian context, an allophone is someone whose first language or mother tongue is not English or French.

Well done Cassandra!! You brought me back to when you and your sister would always ask to go to Jo's house. She would always greet you with open arms and a coffee table full of treats!💕💕💕

Love it!! You’re amazing in what you do, don’t ever stop!! You bring back the best memories!!! Thank you for sharing this beautiful memory. Jo (Giovanna) is very proud of you from up above, that I know for sure! ❤️