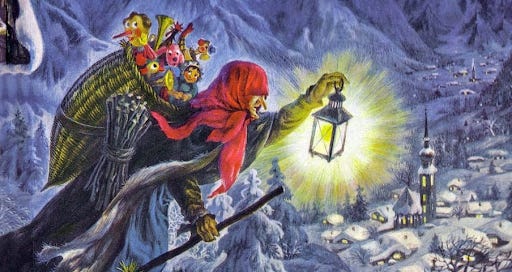

In the middle of the night, in the hours between January 5 and 6, la Befana takes to her broom and flies through the dark, starry sky, bringing sweets, fruits, and coal to children around the world. Growing up, we were told she was like the “Italian Santa Claus.” An old, good witch, with a big nose and grey hair, tied back into her headscarf. She didn’t need a tree, or cookies and milk. Just a stocking, which she would fill with her gifts for you. Of course, la Befana and Santa have two very different histories; she’s not really the “Italian version” of him. But it was simply easier to explain to two little girls, growing up Italian-Canadian, far from the context where Epifania meant something to them.

Epifania is the Catholic celebration that marks the time between Jesus’ birth (Christmas day) and the visit of the three Magi (January 6). The Catholic story of la Befana tells that she helped give directions to the Magi on their way to offer their gifts to the newborn. When they asked her to come along with them, she said no. Immediately regretting her decision, she collected some gifts of her own, and ran out to follow them. Unable to track them down, she shared her gifts with all the children in the hopes that one would be the special child the Magi were looking for that night. She continued this tradition every year on the same day to repent for not having gone with them.

But as I wrote in a previous post about this good witch, “the more you learn about la Befana, the further you go back in time.” Like many of the stories adapted for Catholicism, if you keep pulling at the threads, you will find a deep web of rituals, folktales, and practices that spanned across centuries, geographies, and cultures. That post came out of my growing interest in learning more about this tradition, which I still didn’t fully understand just four years ago when I first published it on my old blog.

As a freelance historian, I have decided to keep my newsletter subscriptions free in order to share my writing with whoever has an interest for the research and reflections in these posts.

If you’ve been following along and have enjoyed my work, liking the posts by clicking the heart at the bottom of the page is easy way to support me.

I learned that la Befana has ties with the Roman celebration of the winter solstice. Her mysterious origins have been traced to Diana, the goddess of the moon, wild animals, and the hunt, Sàtia (goddess of satiety, sufficiency), or Abùndia (goddess of abundance). She’s been compared to similar figures in Germanic mythology, Holda and Berchta.1

From Marybeth Bonfiglio’s writing, I learned that research on la Befana has connected her to Hecate, goddess of magic, the night, the moon, and crossroads: “Befana may predate Christianity and may originally be a goddess of ancestral spirits, forest, and the passage of time. Some identify this wandering, nocturnal crone with Hekate.” Or to the goddess Strina: “also called Strenia (or Strenua), is the Sabine/Roman goddess of the New Year. The goddess of purification, of spiritual, emotional, physical wellbeing. Of new life. Some believe the Befana tradition of bringing gifts is derived by the Strenua cult.”

Digging Deeper

Interestingly, as I also learned from Marybeth’s post, la Befana was appropriated by the Fascist government as part of an effort to connect cultural, folkloric, and religious symbols and practices with nationalism and a strong nationalist identity. Let’s not get it twisted, though. The old crone that brings gifts to children on her magic broom is anything but fascist. In this way, la Befana is a lesson to us to be wary of how folklore and popular culture get swept into far right politics in order to make actions and words more digestible, relatable, and “down to earth.”

La Befana has always been intriguing to me because, as a figure for children, she is kind of terrifying. Scary stories teach us to fear the old hunched woman with the long, crooked nose and unkempt hair zipping through the skies on her scraggly broom. Witches are evil and mean. Right?

Not this witch, I would be told. While she fits every description that would signify that she’s, in fact, extremely evil, I learned, as a child, that she was kind, generous, and genuinely loved children. That her virtues were something I should model.

And actually - going back to fascism for a second - she represents the very antithesis of the far right vision of what it should mean to be a woman: she is ugly, childless, independent, and powerful. It may sound silly or simplistic, but growing up on a steady diet of media that correlates ugliness with evil2, la Befana was one of the first characters to break that mould. As we inevitably enter the period of vision boards (guilty) and resolutions, I hope we can collectively think of ways to bring a bit of Befana energy into our lives.

Continuing along the vein of creepy things that are not so scary after all, I have recently been introduced to a new Epifania tradition thanks to my boyfriend, who is from Desio, a city in the province of Monza e Brianza in Lombardia. There, it is typical to bake, or buy, the papurott. Also known as papurogio, this is a brioche-type sweet bread made in the shape of a doll, complete with what I am told is supposed to be a smiling face. Behold:

Apparently, it was actually invented in Desio. Despite being slightly uncanny and unsettling, it is very good. You can read more about it and find a recipe here (in Italian).3

For me, Epifania is all about citrus. Growing up, along with the off-brand Barbies and trinkets we would receive in our Befana stockings, our nonni always included some clementines. When I saw that Nigella Lawson posted this clementine cake recipe, I knew I had to try it during my week off. Wish me luck!

And don’t forget to hang your stockings tonight.

Cass

Did you grow up with Epifania/Befana traditions? What were they?

Clementine recipes??

How are you embracing Befana energy?

If you would like to support my work further, you can

(it’s like giving a tip) or share Crivello with a friend! Thank you for following, commenting, sharing your stories, and even simply continuing to open these emails week after week.

News

After months of work, my friend and I have finished our colouring book celebrating the Molisan dialect! Each drawing is accompanied by a text pulling on our historical, linguistic, and folkloric knowledge in order to explain the etymology and significance of the words and images. You can order it on my website.

For subscribers, and as a way to practice my tarot skills, I’m offering a one card tarot pull for the new year. It will be a general message for 2025, which I will send via voice notes on Instagram. Send me a dm to coordinate, if you are interested!

I go into more detail in the actual post. I didn’t want to repeat myself for those who have read it before:

And this is nothing new to Disney villains. We can even take it back to the Renaissance, when beauty was seen as a reflection of a woman’s virtue.

I translated the recipe into English:

Ingredients:

250 grams of flour

60 grams of butter at room temperature

35 grams of sugar

A pinch of salt

0.5 grams of vanillina (this is a powder, but I’m assuming you can replace with vanilla extract instead)

20 grams of dry yeast

100 ml milk

1 egg

Raisins for decorations

Preparation:

Warm the milk in a small saucepan, without bringing it to a boil. Turn off the heat and soak the dry yeast in the milk.

Sift the flour and add the salt, sugar and vanillina/vanilla extract.

Mix the ingredients well, adding the egg and butter.

Pour the milk with the yeast into the dough and knead quickly until it forms into a ball. Let rest for about three hours in a warm place, covering with a dishcloth or plastic wrap.

After resting, form the doll, starting with the head and proceeding with the body.

Add raisins as the eyes and buttons.

Brush the surface with egg yolk before baking for 15 to 20 minutes at 180 degrees.