As a freelance historian, I have decided to keep my newsletter subscriptions free in order to share my writing with whoever has an interest for the research and reflections in these posts. If you’ve been following along and have enjoyed my work, liking the posts by clicking the heart at the bottom of the page is easy way to support it. If you would like to support my work further, you can “buy me a coffee” (it’s like giving a tip) or share Crivello with a friend! Thank you for following, commenting, sharing your stories, and even simply continuing to open these emails week after week.

Stagiunà, the molisan dialect form of stagionare, literally means the transformation process that occurs from keeping something, like cheese, prosciutto, or wine, under certain environmental conditions for a particular period of time, allowing it to weather, age, mature or ripen.

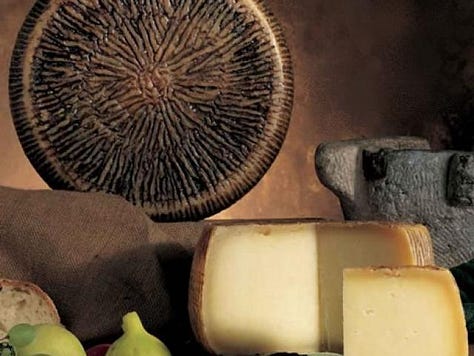

We know about stagionatura: Molisan food is full of aged and fermented ingredients. While I feel like Agnone’s caciovallo has gotten its very much deserved international recognition, there are many more lesser-known cheeses particular to the region:

Formaggio di Pietracatella: I really want to try this one next time I’m in Molise! It’s made from a combination of cow, sheep, and goat’s milk. The forms are aged for minimum two months in the mogie, tuff caves under the historic city-centre used as cantine to preserve products like cheese, wine, and cured meats. Sources mentioning this cheese date back to the 18th century, one even described it as among the best of the province.1

Pecorino: Pecorino romano and sardo are probably the most well-known of this variety, but as with most of the southern regions, Molise has its own production, too. Particularly notable are those made in the Matese area and in Capracotta. Both are made with both sheep and goat milk, and aged for at least two or three months. Pecorino has an ancient and historic presence in Molise, as it is closely related to the transumanza in Alto Molise, dating back to the Samnites.

Tufone: Also aged in tuff caves, this cheese is made from goat milk (particularly kid curd) or cow milk. It’s typical of Alto Molise and aged for 12 months.

Liquore al latte: It’s not cheese, but this liqueur literally called “Milk” is a Campobassan specialty since 1840. It’s made with - you guessed it - milk (from local cows), alcohol, sugar, and natural flavours (I’m assuming part of the secret, original recipe). Ancient and particular processes allow the milk to become soluble in alcohol. From what I’ve seen, Lupacchioli seems to be the main producer of this product.

Different cured meats also abound in the region, and many have continued to make soppressata or capicollo after emigrating. When collecting recipes for Dalla valigia alla tavola, one participant submitted a more “obscure” type of cured meat: la misischia (or muscisca), and ancient technique used by the shepherds in the Matese mountains. The story goes that when a sheep got injured or had been attacked by wolves, for example, shepherds had to think of a way to preserve the meat. We know that nothing went to waste. So, they would debone and dry it in the sun. Prior to drying, the strips of meat would marinate for four days with seasonings of salt, peperoncino, and garlic (another source notes that local herbs like rosemary and juniper were used, too). By storing it in their cantine, this also ensured that their families could have meat throughout the winter. The recommended recipe explained that the strips would be left to soak in water for a day before serving with tomato sauce.

Not to mention the preserved veggies and fruits, stored as sauces, liqueurs,2 jams, and pickles in oil or vinegar (sott’olio or sottaceto). Beyond the tomato sauce, we were reminiscing the other day about all the amazing preserves my nonna used to make from scratch: giardiniera; small red peppers stuffed with tuna, anchovies, and capers (she reminded us that they used to go pick the peppers themselves); the borlotti beans we would shell on the balcony so that she could freeze them for the year…

Thinking of stagionare brings me to many different places. Not just the cantina where items are aged and preserved. Not just the practice of ripening, maturing. But also to the act of enhancing: stagionare, when translated to English, can mean seasoning. Adding the right herbs and spices to showcase the flavours and qualities of your ingredients.

And if we push it a little further, seasoning can speak to the seasons: learning how to navigate the year through the food we eat and how we prepare it. Stagionare, if we take some poetic license with the term, can also be a verb that takes us through the seasons. To understand the tomato, you have to understand the garden; when you understand the garden, the spices, the raw material, you can understand the preserves, the sauce, the cantina; when you understand the cantina, you also know the smells that come and go. Certain times of the year smell of fermented grape; other times smell like prosciutto; others, milky. This knowledge is all related, and expands beyond the recipe, into lived experiences, through festivals, feasts, saint days, and traditions, many of which are obsolete to us today, but which our ancestors used to mark the passage of time. What can we learn about ourselves and our community by tracing the stories of the seasons, past and present?

One of my favourite cookbook finds is Anna Del Conte’s A Casa: Seasonal Italian Home Cooking, which I picked up last year at the incredible Bonnie Slotnick Cookbooks in New York. Organized by season, Del Conte tackles the dinner party with a particular focus on balance and context for the place and time each meal will be served.

Seasons… I begin to wonder if they still exist. As far as food and produce are concerned, they hardly do, and in the last few years even the seasons themselves seem to have changed!3 […] Some might say how lucky we are, yet I miss the time when the months were marked by the different produce that appeared in the shops and markets. And just as there were seasonal vegetables, so there were seasonal dishes.4

As we’ve seen, this goes beyond vegetables, too. Most cheeses are made year-round, though some are said to be better when made in the spring, due to the animal’s diet at that time of year. Many cured meats are made between November and January. Liqueurs, preserves, sauces, are made at the end of summer or early fall. With this in mind, Del Conte provides a variety of seasonal menus throughout the cookbook for between four to thirty people.

Published in the 90s, I think we can say that, since then, there has been a shift back towards seasonality (maybe I’m noticing this because I’m also in the “season” of my 30s, and my friends and I reflect on these things). I would be curious to know if you agree. Recently, Olivia Cavalli published her cookbook Stagioni: Contemporary Italian Cooking To Celebrate The Seasons. Joshua McFadden's Six Seasons: A New Way With Vegetables (2017) is a classic for working with seasonal veggies in the kitchen. I’ve seen many new restaurants focus on local and seasonal produce. I’ve mentioned this before, but seasonality was another direction we had thought of for Dalla valigia, seeing as so many of the recipes’ oral histories focused on feasts and specific times of year.

In many ways, this newsletter is a part of my own “stagionatura.” I talk about this often with those close to me, but I feel like there have been many moments over the last five years where I’ve thought: “Ok, I’ve made it - everything will fall into place now.” Long story short, I have stopped thinking that. Mainly because most of my best laid plans have not gone as expected (work and career-wise, I mean). This year, I made some choices for myself: to pursue my writing and research, to create more art, to work in my field through freelance contracts, to rebuild my network after feeling lost and divorced from the work that fulfills me for quite some time. It’s been a test of patience, for sure. I know that this isn’t built overnight and I need to continue to work hard on myself and my practice. That said, your support as one of the growing readers of this little corner of the digital sphere has meant the world to me.

You, too, are a part of this new season.

Not to sound cheesy, but I really think that my priorities and perspective changed when I hit my 30s. As I’m sure they will continue to do as I age. Life is a cantina.

Cass

See below for monthly tarot pull, footnotes, and resource list.

Monthly Tarot Read

Each issue will include a tarot pull reflecting on the topic of the newsletter.

This combination really hits home for me at this moment. It’s officially summer here in Montreal and I’m feeling that shift in spirit. After last week’s heat wave at 60+% humidity, the sun feels invigorating. During the summer, plants and crops (hopefully) flourish. The Sun card, in its youthful and bright energy, reminds us to radiate our most authentic selves; that there is abundance to be uncovered; that there is joy around the corner. The Eight of Pentacles, the apprenticeship card, is about commitment and effort. Together, I read them as highlighting the power of passion, honesty, and love in everything we work towards. Whatever comes from that place, speaks for itself.

Summer, for many, represents a time of rest, but don’t forget that our gardens need to be watered, extra leaves need to be snipped (so that our tomatoes get all that good sunlight), and ripe fruit needs to be picked to leave room for more to grow.

“Il formaggio di Pietracatella è tra i migliori della provincia,” quoted in ERSAMolise, “Atlante dei Prodotti Tradizionali della Regione Molise,” Anno IV no. 1-2, 2003, from Longano Francesco, “Viaggio dell’Abate Longano per la Capitanata,” 1790, 83-161.

Typical Molisan liqueurs include amari, nocino (made with walnuts), and ponci (sweet liqueurs made with herbs and fruit peels; or even coffee).

Note that this book was published in 1992.

Anna Del Conte, A Casa: Seasonal Italian Home Cooking (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 3.

Resources

Cavalli, Olivia. Stagioni: Contemporary Italian Cooking to Celebrate the Seasons. London: Pavilion Books, 2022.

Crupi, Jaclyn. Garden Like A Nonno: The Italian Art Of Growing Your Own Food. South Melbourne: Affirm Press, 2021.

Del Conte, Anna. A Casa: Seasonal Italian Home Cooking. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

ERSAMolise, “Atlante dei Prodotti Tradizionali della Regione Molise,” Anno IV no. 1-2, 2003

McFadden, Joshua. Six Seasons: A New Way with Vegetables. New York: Artisan, 2017.