As a freelance historian, I have decided to keep my newsletter subscriptions free in order to share my writing with whoever has an interest for the research and reflections in these posts.

If you’ve been following along and have enjoyed my work, liking the posts by clicking the heart at the bottom of the page is easy way to support it.

Friday was Sant’Anna, Saint Anne’s Feast Day, celebrated in multiple comuni in Molise. Including Cantalupo nel Sannio, where three of my nonni are from, because Sant’Anna is one of their patron saints along with San Salvatore. This history lingers on in my family’s names: Nonno Sam (Salvatore), and both my mom and my middle names from Sant’Anna.

Saint Anne, in Christian tradition, is Mary’s mother, Jesus’ grandmother. Patroness of mothers, grandmothers, unmarried women, childbirth, those seeking to get pregnant, and educators. Many villages in Molise also claim her as their protector and a symbol of hope in the wake of disaster.

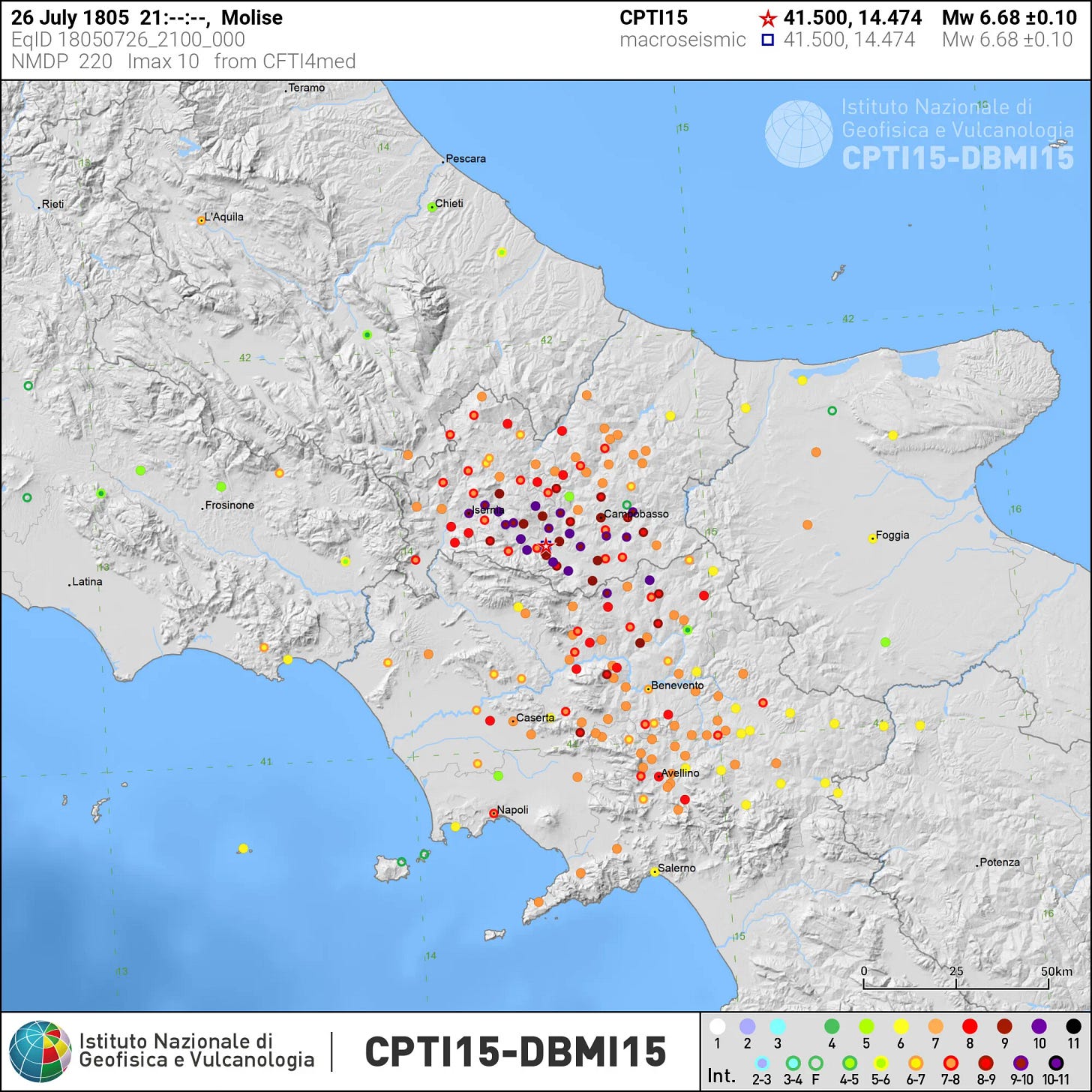

On July 26, 1805, a devastating earthquake hit the region and affected many of the comuni, including Cantalupo. Four to six thousand deaths have been estimated. Since it happened on Saint Anne’s day, the survivors thanked her for defending them. In Cantalupo, it is said that though the town and church crumbled, the statue of Sant’Anna remained standing.1

In the past, Sant’Anna would have been celebrated on this day with a candlelit procession. Today, the comune plans a whole week of religious and secular activities to mark the occasion. Including DJ sets and musical performances, traditional food prepared on the spot, booths selling candy, masses, processions, and hikes. It all culminates in a fireworks display, as has become Saint day tradition across southern Italy. Being in Cantalupo in July and August means falling asleep to the sound of fireworks in the surrounding villages.

Sant’Anna is also celebrated in Campolieto, Capracotta, Pescolanciano, Pietracupa, and by the associations in Montreal. Just a few weeks ago, we went on a pilgrimage to Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré with the Cantalupo and Santa Maria associations. And last weekend, we celebrated the annual Saint Anne picnic. I’m not a particularly religious person, though like many Italian-Canadians, was raised Catholic. Having been involved in Italian association life from childhood, I have developed, over time, my own relationship with these practices.

Since the pandemic, I’ve often seen a shift in younger generations’ approach to these associations and local identities. In the age of micro-identities booming online, as David Herbert & Josh Bullock describe in their paper “Reaching for a new sense of connection: soft atheism and ‘patch and make do’ spirituality amongst nonreligious European millennials,”2 said millennials (in our case, Italian-Canadian and American) are able to find their own path and understanding of folkloric, religious, and traditional practices by connecting with them in different ways, with knowledge of the ties to and history of Catholicism in these communities, but without necessarily strict adherence to them.

To survive, traditions have to adapt and evolve over time, as each generation responds to changing contexts and perspectives. While, of course, ties to religion remain, and there are certainly third-gen (and beyond) practicing Catholics, leaving room for interpretation allows more of us to feel a part of the community.

I grew up actively partaking in processions because of these community ties. As I got older, they embarrassed me. Now, I would gladly take part in them again because, personally, they represent a space to bond with older generations. The cultural and aesthetic specificities also make them special: I can learn about, understand, and engage with the symbols of my heritage.

Probably the most iconic Sant’Anna procession and celebration - in Molise and Montreal - is Jelsi’s Festa del grano (Grain festival).

Another town affected by the 1805 earthquake, Jelsi organizes a procession around the statue of Sant’Anna as part of a tradition in continuing to ask for her protection and blessing, through devotion around grain. According to the town’s history, dedication of this festa del grano to Saint Anne was further cemented after an 1814 “hurricane” was unleashed on the area on July 24 and 25. It was seen as another message, or “intervention,” from the “Great Mother.”3

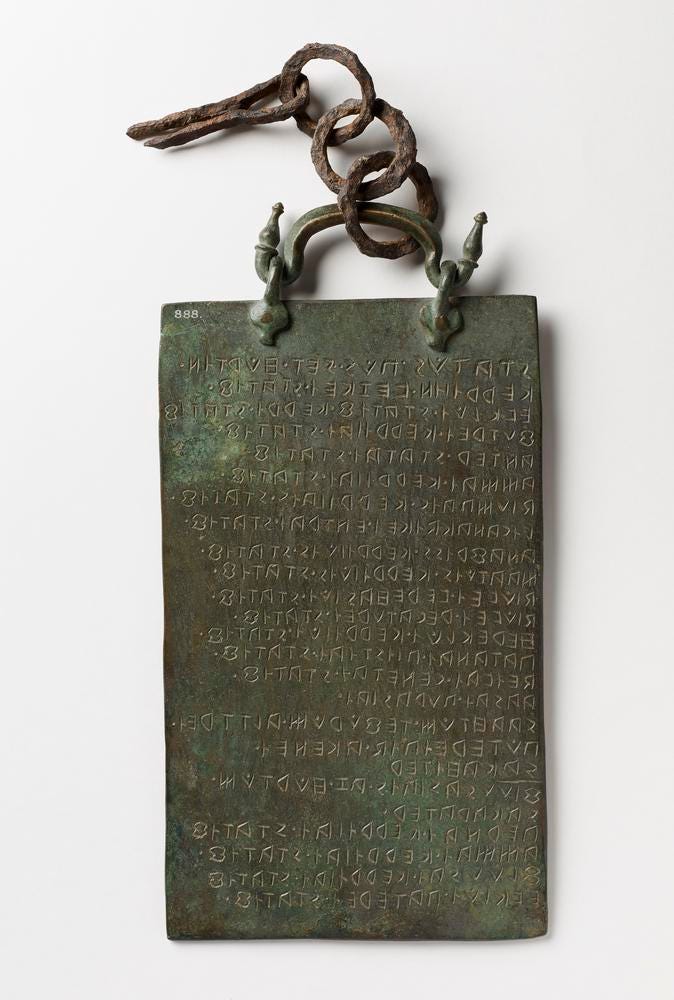

It’s unclear whether the custom of offering ears of wheat to Sant’Anna existed before these natural disasters. Though the practice of identifying plants as special totems has existed in many cultures and religions. In Molise, a historically agricultural region, wheat has been an important symbol since the Samnites ruled the territory. Evidence of our special relationship with the grain has been found in the Tavola Osca, a bronze tablet dating to the 3rd century BC, discovered near Agnone.4

The tablet lists seventeen deities, many of which are related to grains/cereals, including Kerrì (Ceres), goddess of grain.

As many as nine other deities bear the epithet kerrìio and refer to fertility cults - associated with the earth but, in some ways, also with humans - whether relating to springtime (Fluusaì kerrìiaì, “flora cereals”) or early sprouts (Futreì kerrìiaì, aka Persephone), or motherhood (Ammaì kerrìiaì, possibly meaning Grain Mother). Even Hercules is linked to cereal (Hereklùì kerrìiùì).5

The Samnites worshiped these gods of grain, and Diùveì piìhiùì (Jupiter), irrigator of the earth and ruler of water and springs. This deep connection to wheat was later made evident in Molise’s old coat of arms, which celebrated its grain production6:

Wheat, therefore, was already linked to fertility and life. The same realms of human existence that Sant’Anna reigns over. In Catholicism, she is the “highest representation of fruitfulness,” the mother of mothers.7 Grain Mother. Mother Earth.

In Jelsi, the original devotion to Sant’Anna involved transporting grain along the main road of the village with the traglia (a kind of wheeless cart, like a sleigh), pulled by men and donkeys. Today, in Jelsi, and across the ocean in Montreal, the community celebrates this Mother by meticulously decorating wagons and sculptures with wheat, which are then paraded through the streets with prayers and music. Anyone that wants to participate in the parade must commit weeks of their time to these beautiful decorations, the grain an expression of devotion to their patron saint. This procession has been recognized as Patrimonio immateriale d’Italia (Italian Intagible Heritage) by the Istituto Centrale per la DemoEtnoAntropologia.

Women, traditionally, decorate the streets and piazze with wheat garlands.8 The sculptures, like modern celebrations, are both religious and secular. Human and divine. Pagan and Catholic. They represent fertility, domestic labour, Sant’Anna and her daughter, Maria, animals, and agriculture. In Montreal, people of the Jelsese association have even made wheat sculptures of local landmarks, like the Casa d’Italia. Here, the festivities take place over three days, organized by the association. The night before the procession, they mimic the tradition of the harvest, done one month before the feast in Jelsi itself:

After the day’s work, everyone gets together to eat the “farmer’s breakfast.” In Molise, contadini typically ate eggs and peppers for their first meal of the day. In Jelsi, their dish is called u’ funnateglie. Eggs are poached in a sauce made with salsicce sotto sugna (sausages preserved in lard), peppers, and tomatoes.9 Served with a side of fresh bread and cheese, the name funnateglie is derived from the act of soaking the bread in the savoury sauce.

While this meal doesn’t happen after the wheat harvest here, a communal meal of funnateglie is organized at a local park. Under a spacious tent equipped with six gas burners and an array of terracotta dishes, skilled cooks from the community work their magic, frying and simmering the humble ingredients.

The Festa del grano weekend is the highlight of the year for the association. As is the week-long feast for Jelsi. Thousands attend, coming from across Molise. There, they have even created a museum, which houses sculptures from processions past. A new initiative, part of Italy’s push towards roots tourism, is also promoting festivals and feasts, like the Festa del grano, through social media campaigns and travel itineraries. These towns have clearly always had this in mind in their own humble ways, through small museums, like the one in Jelsi, and the recent boom of B&Bs opening over the last decade.

While I have often thought about the plight of Molise, nicknamed “the region that doesn’t exist” by fellow Italians, and recognized that increased tourism is warranted and needed, I also worry about its consequences.

’s series on over-tourism in Italy has made me reflect further. On the one hand, I hope that turismo delle radici (roots tourism) promotes a more responsible kind of tourism. One that encourages a real connection to the people and places you visit, whether you are from there or not. But I am scared about the future of tourism in Molise because there’s obviously a goal to make it a big part of the region’s economy.It’s a beautiful region with deeply historical traditions, even older than the Roman Empire. These traditions are linked to the territory, the seasons, the spiritual. It deserves to be seen, known, and respected. But, what if it goes the route of Puglia, for example? There, the locals (and tourists) deal with the same problems with resources and infrastructure year after year. Problems Molise already faces.

What will happen to this place if over-tourism spills into it? What will it, and its traditions, become beyond the tourist attraction? What will improve, what will deteriorate? We know, by know, that tourism comes with a cost. Currently, some of the most historic sites in Molise are barely even evident or accessible to the public: Saepinum, the remains of a Samnite settlement, must be accessed through the parking lot of a restaurant with a sign so small, you drive right past it on the highway; to visit the ancient ruins of a theatre in Pietrabbondante, you have to hike through an overgrown forest path.

While traditions evolve, they still need to be embedded in a certain context to survive with meaning. Using these feasts as spectacles for tourism do not add to that meaning. Is there a balance we can strike? What ethical approaches can we bring to the table?

Interestingly, this is, in a way, a question that comes up for the associations here, too. As many face dwindling membership, many of their parties and activities include forestieri (foreigners, aka people not from or descending from the town the association represents). Within these groups, conversations around purpose and audience have taken centrestage. Who are we working for? What do these events accomplish? Who is the audience, and what does that mean for our future?

I love Molise. I don’t want to guard it jealously from others. But maybe I do, just a little.

Cass

See below for monthly tarot pull, footnotes, and resource list.

If you would like to support my work further, you can

(it’s like giving a tip) or share Crivello with a friend! Thank you for following, commenting, sharing your stories, and even simply continuing to open these emails week after week.

Monthly Tarot Read

Each issue will include a tarot pull reflecting on the topic of the newsletter

The Devil - vice, tyranny, indulgence - and Four of Corta (Rigatoni) - celebration, gathering, sacrament. These are the descriptions given by the Pasta Tarot’s creators in the guide they’ve included with the deck. And they really speak to my thought/worry spiral on the fate of traditions like the Festa del grano under the looming spectre of over-tourism. While, traditionally, the Devil does not need to necessarily represent negative outcomes, it does speak to the shadow, the dark side. I see these cards as the two faces of tourism we need to complicate: one being the over-indulgent tourist who takes, consumes, destroys without appreciation or respect; the other being the ideal ethical tourist (who may not exist), who treats every trip as some kind of pilgrimmage to “find themselves,” eat/pray/loving their way through the landscape. Both are caricatures.

Instead, I appreciate Wyant’s suggestions for being a better guest when participating in tourism:

be an educated traveler

stop with the bucket list mentality

avoid global corporations, instead support local businesses

don’t travel to post and boast

Though my family is from Molise, I am a visitor there. I’ve realized that being embedded in the community here, doesn’t always translate to the context there. Many emigrants from my nonni’s generation also complain of being labeled forestieri whenever they visit their hometowns. But it’s hard to imagine them as tourists. When they visit these places, they stay with family, they go to church and the bar, they chit chat outside. They are re-embedded in the community they left a lifetime ago. I have the privilege of that proximity, too. I realize not everyone can have this. I have the urge to not consider myself a tourist, either. I don’t know if this is wrong.

Beyond the individual tourist, I think these cards can also represent the tourism industry at large. When the sentiments represented by the Four of Corta become a facade - manufactured community, gathering and celebration as spectacle, rather than meaningful and historic - the slope towards the “dark side” becomes increasingly steep. There is selfishness in both not opening up to people and in letting everything become an attraction. It’s finding the nuance that’s difficult. I wonder if (and how) the examples of over-tourism we are seeing across Italy will be taken into account as Molise ramps up its own industry.

Wikipedia has a table breaking down the effects of this terrible earthquake: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1805_Molise_earthquake.

Herbert, D., & Bullock, J. (2020). Reaching for a new sense of connection: soft atheism and ‘patch and make do’ spirituality amongst nonreligious European millennials. Culture and Religion, 21(2), 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14755610.2020.1862887.

Oscan was the language spoken by the Samnites.

In the eighteenth century, Molise was called the “granary of the Neapolitan Kingdom.” https://www.comune.isernia.it/it/page/parte-i-la-festa-di-santanna.

Ibid.

Very similar to shakshuka! There are obviously historical ties there.

Further Resources

https://festedelgrano.net/en/jelsi/

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Festa_del_grano_(Jelsi)

https://www.regione.molise.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/11460

https://www.turismoinmolise.com/

The UN on “ethical tourism”: https://www.unwto.org/global-code-of-ethics-for-tourism

Luda Berdnyk, “Does the Ethical Tourist Really Exist?,” MAHB, February 26, 2019: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/ethical-tourist-really-exist/.

What a lovely, thoughtful, post about Molise💛. Thank you for the mention. Did you intend to be formal, using my last name, or did you think my last name is my first name? 😉

I enjoyed reading this. The peppers and eggs dish is right up my alley. I have the same concerns about Abruzzo, as well as Molise, as my paternal grandmother was from Isernia and it is a breathtakingly beautiful region. The appeal of these two lesser known regions is their natural beauty, their enduring traditions, and their relative lack of crowds (except for the beaches in summer). I heard that Stanley Tucci was in Abruzzo filming an episode of his show, and I have very mixed feelings about that.