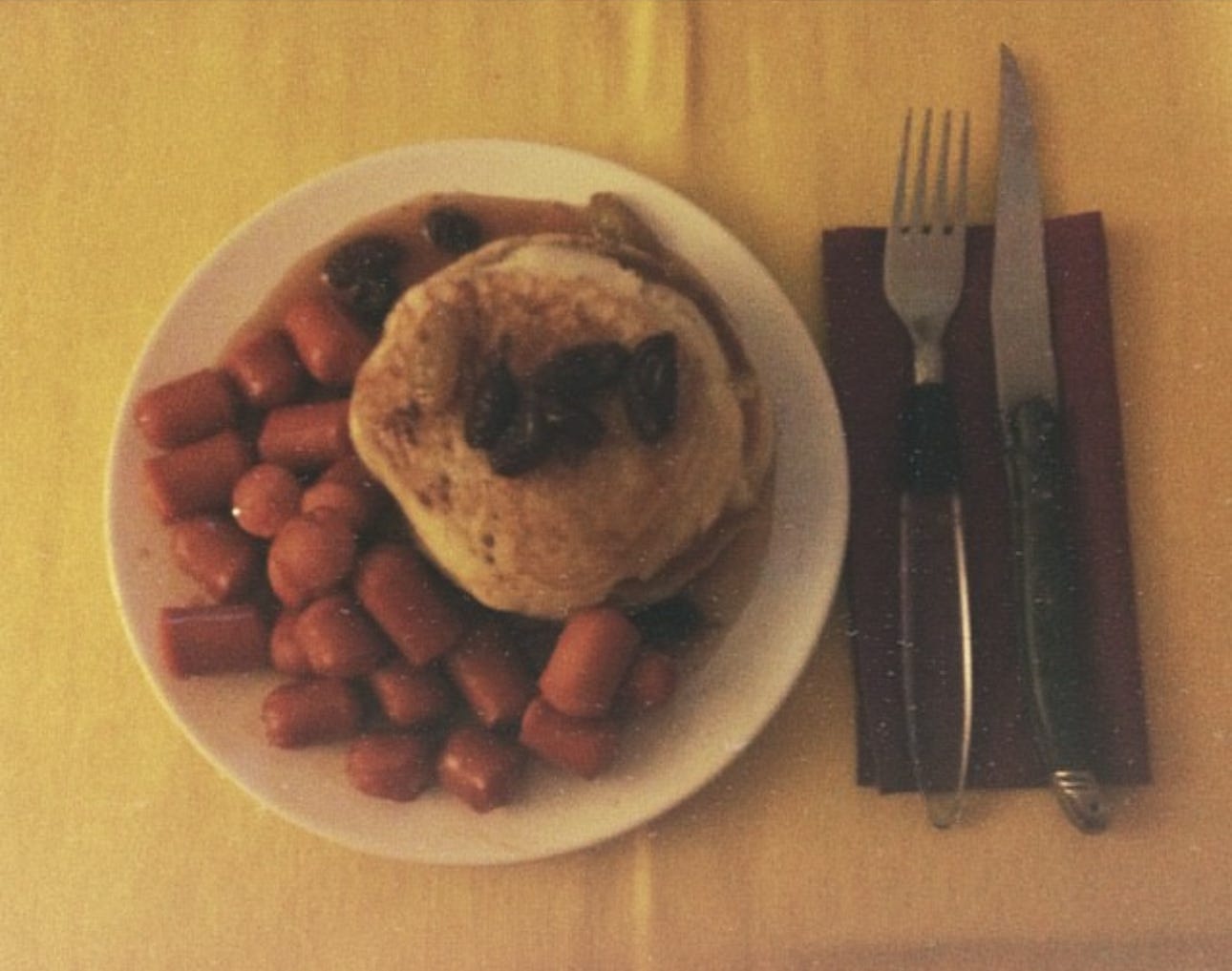

If you grew up in Québec, I am willing to bet your first school field trip was to a cabane à sucre (sugar shack). That field trip set the tone for me. For years to come, I would compare every cabane à sucre to the one from that day. There, I discovered what has remained a lifelong favourite: saucisses cocktail dans le sirop. Basically mini hot dogs in a “soup” of maple syrup. Many years later, when I found myself away from home for a semester abroad, I would use the maple syrup my family sent me to make my own version. With a side of pancakes, of course. We never had mini hot dogs in syrup at home; it’s strictly cabane à sucre fare. But I craved them when I craved home.

Back on that field trip, wide eyed and overwhelmed, I filled my plate with pancakes, bacon, hot dogs, potatoes, scrambled eggs, fèves au lard (like baked beans). I smothered it all in maple syrup, in disbelief that we were allowed to eat all this sugary goodness. What a day!

Since then, between friends, family, and the Italian associations, we made the trip to a sugar shack almost every year during le temps des sucres, sugaring season. Running from late February to early April, it is also a celebration of a sweeter season ahead: we made it out of the worst of winter, the birds will soon return. Meanwhile, around the same time in Molise, different towns and villages are preparing to celebrate Carnevale, a festival with inumerable different iterations across the entire country, the most famous of which is probably the Carnival of Venice. In fact, that’s the only carnevale I grew up knowing. Until I started researching more about Molisan folklore and history, I didn’t know we had our own versions of this ancient celebration. It seems like, here, our diaspora community adopted le temps des sucres as its placeholder.

Molisan Carnevale traditions range from the dark and creepy to the extremely silly.1 Since 1955, the town of Larino has organized a parade of decorated floats. First made from whatever the community members could find, after 20 years of the carnival parade, a committee got together to create the enormous animatronic floats the Carnevale di Larino is known for today.2 In Vinchiaturo, they organize the Pezza de casce race, where the goal is to roll a wheel of parmiggiano through the streets faster than the other team. We then veer into the more pagan and ancient practices: men dressed as deer, bears, and devils perform in the piazze of Castelnuovo al Volturno, Jelsi, and Tufara, respectively.

If you’ve been following along and have enjoyed my work, liking this post by clicking the heart at the bottom of the page/e-mail is an easy way to support me ❤️

These performances are based in a magical folklore, speaking to the feelings of uncertainty, hunger, and fear faced during the winter months. L’uomo cervo (man-deer) destroys everything in his path until he is defeated by the forces of good; il diavolo (devil) di Tufara’s frenetic and unpredictable movements leave the public uneasy; l’uomo orso (man-bear) must also be captured and tamed in order to herald a fertile spring. Witches, hunters, and wizards figure prominently, as do ancient mythodologies repurposed into these fairytales come to life. There are echoes of Saturnalia (the ancient Roman celebration for Saturn, god of the harvest) and Anthesteria (the ancient Greek festival for Dionysus, marking the beginning of spring). The modern-day pagan practices recall elements of sacrifice, a world turned upside down, things not being as they seem.

Food and drink were significant to the ancient festivals, but also to the eventual Catholicisation of carnevale. Mardi gras (fat Tuesday; or pancake Tuesday—we’ll get back to this), for example, is the last day before Lent. A day of indulgence, those who celebrate are encouraged to eat fatty and hearty foods before the 40-day fasting period.

There’s another layer to carnevale traditions in Molise, though. The figure of la pacchiana.

The pacchiana is a peasant woman, dressed in the typical costume of her village. Often ornate and intricate, from her hairstyle down to the embroidery of her apron, the pacchiana dons her traditional outfit on special occasions, like carnevale. When I interviewed her for the cookbook, Filomena Di Giorgio (her mother is in the photograph above) explained how the figure of la pacchiana is tied to Bojano’s carnevale celebrations, particularly in relation to the typical sweets, conecchiele:

We never let go of the traditions, neither I nor all my sisters. This dessert comes from Bojano from... it's truly, truly ancient. It was made on the last day of Carnevale, which, in Bojano, you celebrated by dressing up in Carnevale costumes, especially the pacchiana of Bojano. In short, people passed by the houses to greet us and we offered this dessert and a coffee. And so, it was the dessert eaten on the last day of Carnevale. But logically, here today I do it on the occasions that arise, you know. And above all in my family, it has remained truly a sweet... that recalls memories more than anything else.3

Also known as crispell’, frappe, chiacchiere, scaroletti, gnocchetti, and crostoli4, this fried sweet is made across Italy and beyond (the French beignets de carnaval are extremely similar). Dough is cut into thin strips and looped into a particular design. The beignet is then fried and, once cooled, drizzled with honey or powdered with icing sugar. The modern recipe is inspired by the “truly ancient” Roman frictilia, which were fried in pork fat for Saturnalia and Bacchanalia.

Other sources online also link the pacchiana to rituals of sharing food, some around the epiphany, clearly related to the folklore of la Befana. I’m still doing some research on la pacchiana and will hopefully be able to share some more information in a future newsletter.5

Besides timing, then, I see many similarities between carnevale and le temps des sucres here in Québec, with a melding of different Christian and pagan traditions, and the history of colonialism in this country.

The practice of tapping maple trees for sap has Indigenous origins in the traditional territories of the Haudenosaunee, Anishinaabe, Abenaki, and Mi'kmaq Nations. During the period of ziisbaakwadoke-giizis (the sugar making moon in Anishinaabemowin), Indigenous peoples have produced maple syrup for generations, “to cure meats, as a sweetener for bitter medicines, […] as an anaesthetic”; for its nutritional values, as it contains minerals like “phosphorous, magnesium, potassium, iron and calcium”; and “as a trade item in the form of dried, portable sugar slabs.”6 Now presented (and marketed) as a Québecois tradition, the French-Canadian “origins” of le temps des sucres comes from colonisation of peoples and their practices. By the 1970s, maple syrup production became a powerhouse industry, spawning the creation and proliferation of commercial sugar shacks.7 The experience extends beyond the meal and includes: a horse-drawn carriage ride through the maple trees (for an additional fee), farm visits, and a DJ set with various line-dances to help you digest after eating.

Usually, when you go with an Italian association, there are even late afternoon panini provided before heading home. Actually, when I spoke to my parents about our community’s affinity for cabane à sucre, my mom explained: “Your nonno only like the oreilles de crisse. He didn’t eat anything else; we had to pack panini for him.” Nevertheless, we packed the dining halls every time.

This is exactly the type of thing I want to keep digging into, because we need to go through centuries to get to this table. Through ancient paganism, European Christianisation and colonisation, Indigenous knowledge, immigration, assimilation, adaptation, folklore, religion, politics, we arrive at nonno Michele’s love for oreilles de crisse. Not to mention the capitalist desire to market authentic experiences to “outsiders.” Even the Québec City carnival outs itself when writing about this tradition: “In 1893 a group of businessmen led by former Québec premier Joly de Lotbinière started a huge carnival to brighten up dark winter days and attract tourists.”

In “Pancake Politics,”

dives into issues of class and authenticity around syrup and other pancake garnishes:Nutritional outcomes aside, these are all perfectly fine pancake garnishes; there is no right or wrong way to eat a pancake (I’m partial to sorghum with a sprinkle of brown sugar on top). Except, there is, of course, because pancakes are emphatically American and we’ve attached lots of feelings and morals to them and expect them to look, smell, and taste a specific way. We feel so strongly about the rightness of pancakes and syrup that we had to invent a maple syrup stand-in. And when others who couldn’t access or afford that imitation attempted to use other ingredients that had on hand, we looked down our noses at those less-American attempts.

Carnevale and Cabane à sucre traditions are equally wrapped up in these concerns. But as I have traced just some of the historical evolutions and changes in this newsletter, they continue today. As we were deciding which cabane à sucre to visit this year, my dad brought up the one affiliated to Fromagerie Fuoco, a bufala cheese producer in Québec. He said: “It’s cabane à sucre, but with an Italian twist.” In fact, according to their menu, you can order a platter with Italian sausages or mozzarella fdi bufala along with the traditional sugar shack fare. There are also cabanes à sucre that now offer Halal menus.

Thinking about class and the post-WWII Italian immigrant community is a whole other newsletter. But as a final reflection for today, cabane à sucre is also a relatively affordable outing, especially when you consider the amount of food you get. Not to mention the familiar cucina povera ingredients: pork, eggs, lard, beans. I think that both these facts helped bridge the connection between the community’s ancestral and adopted traditions.

In 2016, the Associazione Sant’Anna di Cantalupo celebrated its 50th anniversary. People from Cantalupo, in Molise, were invited to join us as we celebrated our community in Montreal. As a gift, the association prepared maple leaf shaped bottles, filled with maple syrup, engraved with Sant’Anna holding her child, Mary (header image above). The offering represented our entangled identities, our complex roots, in a blend of the sacred and profane. It’s kitsch, una pacchianata. It’s perfect.

Cass

See below for monthly tarot pull, further sources, and footnotes.

If you would like to support my work further, you can

(it’s like giving a tip) or share Crivello with a friend! Thank you for following, commenting, sharing your stories, and even simply continuing to open these emails week after week.

Monthly Tarot Read

Each monthly issue will include a tarot pull reflecting on the topic of the newsletter

For Christmas, I made this deck of oracle cards for some friends and family members. The 44 cards are made up of symbols both sacred and profane that are close to Italian-Canadian identity, rooted in the history and kitsch of that culture. Also inspired by history from the Samnites, Ancient Rome, and Molise. They even came with a little guidebook. One of my projects for this year is to create a second version available to anyone. The deck has 7 themes: alla tavola (around the table), le cose della nonna (nonna’s things), le erbe (herbs), le feste (feasts), i santi (saints), gli dei (gods), and il paesaggio (landscape).

The Fortuna card comes from the dei theme. Like the Wheel of Fortune Tarot card, Fortuna represents cycles, change, destiny, and the forces of luck and fate. It signifies that life is constantly in motion, with periods of ups and downs, sometimes beyond our control. As the goddess of luck and fate, Fortuna’s wheel turns without warning, bringing both fortune and misfortune in constant cycles.

The themes explored in the pagan and ancient carnevale traditions above also confront the absurdity and ucertainty of life through the veneration and celebration of gods, animals, magic, and seasons. They speak to the fact that, like the man-deer destroying eveything in his path before being captured by the forces of good, sometimes things needs to fall and break before making space for new awakenings.

The cycles of nature, the seasons, and life are further reminders that we don’t only break and rebuild once: these are perpetual.

Further Resources

Diavolo di Tufara official website: https://www.ildiavolotufara.it/.

Evans, Tony Tekaroniake. “The Indigenous Origins of Maple Syrup.” American Indian. Winter 2022, Vol. 23 No. 4. https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/Indigenous-origins-of-maple-syrup.

Italea Molise events: https://italeamolise.com/en/events/.

“Ninaatigwaaboo (Maple Tree Water): An Anishinaabe History of Maple Sugaring,” The text for this exhibit was first published by Alan Corbiere in the Newsletter for the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation (6:4 May 2011): https://grasac.artsci.utoronto.ca/?p=136.

Spina, Maria R. “La mappa della pacchiana.” https://famigliabojanese.wordpress.com/la-mappa-della-pacchiana/.

Spitilli, Gianfranco. Tra uomini e Santi. Rituali con bovini nell’Italia centrale. squi[libri], 2011. https://www.academia.edu/10625915/Tra_uomini_e_Santi_Rituali_con_bovini_nell_Italia_centrale.

Uomo Cervo official website: https://uomocervo.com/.

For a more complete list than I will be able to get into here, you can check out Turismo in Molise: https://turismoinmolise.com/carnevale-molise/.

I’ll get into it, but carnevale has a long history in Italy, beginning way before 1955. It’s interesting that this parade has been selected as part of the 27 “historic carnivals of Italy” because, technically, it hasn’t been around that long. We can see the invention of tradition in real time here: it only takes a few generations.

I translated from the original Italian: "Le tradizioni non le abbiamo mai lasciate, ne io ne tutte le mie sorrelle. Questo dolce viene da Bojano da... veramente, veramente antico. Si faceva l'ultimo giorno di Carnevale, che a Bojano si vestivano da Carnevale, sopratutto la pacchiana di Bojano. Passavano per le case per salutarci e si offriva questo dolce e un caffé, insomma. E allora, era il dolce dell'ultimo di Carnevale. Ma logicamente, io qua oggi lo faccio alle occasioni che incontro, insomma, sa. E sopratutto nella mia famiglia è restato veramente un dolce... del ricordo più che altro."

Since I know this type of dessert is popular across Italy, I did a little survey in my Instagram stories asking folks to submit what their family calls them. These are responses that come from friends who have roots from north to south. Probably not comprehensive, but they give a good idea of the diversity.

An aside here, but the Italian term pacchianata has come to signify something that is vulgar, gaudy, and tacky. Like a person trying too hard, and failing, at seeming elegant. Think old money aesthetic vs. the ludicrously capacious bag. Again, there is more research to be done here, but it must come from sentiments of looking down upon the intricate pacchiana costumes in order to put peasants in their place. Similar to the use of terronata today, as a term to mean something tacky done by “terroni”, people from southern Italy, which is interesting because then it also brings that north/south/urban/rural history into play.

Tony Tekaroniake Evans, “The Indigenous Origins of Maple Syrup,” American Indian Magazine, Winter 2022, Vol. 23 No. 4, https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/Indigenous-origins-of-maple-syrup.

“Aux origines du temps des sucres,” Radio-Canada, 19 mars 2021, https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1777976/cabane-sucre-histoire-fabrication-sirop-erable-archives.

I have so many thoughts after reading this! I learned a few years ago that Maryland used to be one of the main suppliers of maple syrup to the US. Due to the effects of climate change, most people don’t even consider Maryland when they think of maple syrup.

Reading about carnival in Italy in your post also got me thinking about how so many cultures around the world have some kind of pre-religion festival for goodwill, abundance, or cleansing, and how some of those cultural festivals have been syncretized through colonization. It’s interesting to notice the ways we celebrate differently for the same reasons.